The Town Warburg

Warburg – History of the Town

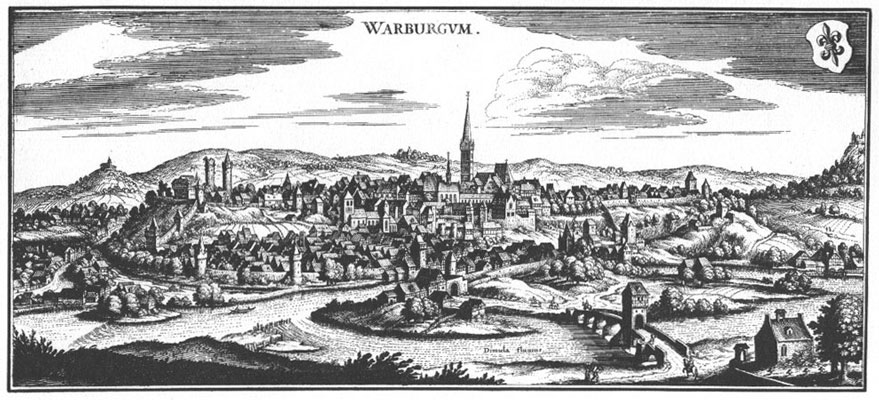

A print of a facsimile from Matthaeus Merian from the book “Topograhia Germaniae”. The view of Warburg is from the middle of the 17th Century.

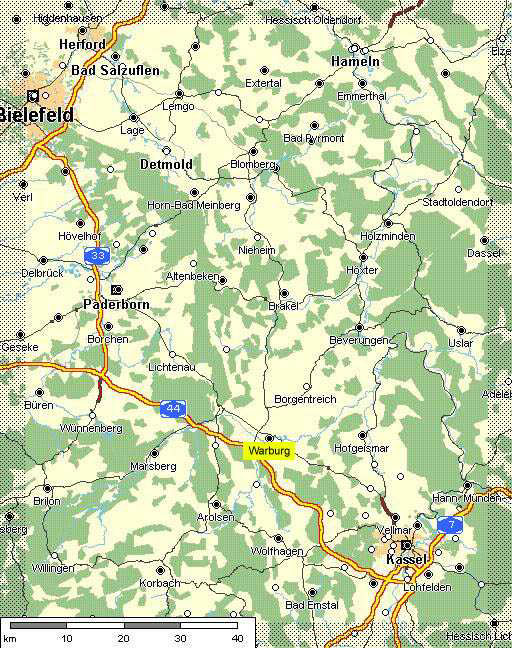

The town of Warburg is situated in the south-eastern area of the former Prussian administrative province of Westphalia, where Westphalia, Hesse and Waldeck meet, often so important for its historical development. Two cultural and economic centres developed at an early stage in what is now Warburg: the old town (Altstadt) and the new town (Neustadt).

The old town dates back to a castle dominating the Diemelfurt. Various findings on the castle mound indicate habitation as early as the 9th or 10th century. During the 11th century, under the shelter of the castle which became dilapidated and uninhabitable towards the end of the 16th century and was pulled down in 1830, a totally unplanned commercial settlement developed at a crossing point of old trade routes. This situation remained until the town and state ruler, the bishop of Paderborn, developed the old town according to a plan. It is documented that the old town of Warburg already possessed a town charter in 1191.

In 1281 the Paderborn bishop Otto von Rietberg brought the first Dominicans to Warburg and gave them the small vineyard at St. Marien for the establishment of a settlement there. In 1283 he also gave them the old town parish church “Sancta Maria in vinea” including bells, graveyard and the adjacent hillside known as the Ikenberg.

The citizens of the old town were very angry and bitter about this gift by the bishop because they were allocated the new town church at the same time. The protest caused a row when the citizens of the old town violently attempted to expel the Dominican monks from the possessions given to them. It was only when the bishop threatened the ringleaders with interdict and excommunication that peace was re-established after lengthy negotiations and a contract was signed in 1287 which ensured that the Dominicans remained and that the old town parishioners got a new church. This was called “ad visitationem beatae Mariae virginis” (visit of Mary to Elisabeth). The Dominicans remained hereafter in undisturbed possession of the church of St. Maria in vinea and the hillside where they shortly afterwards erected a monastery church on high retaining walls. On 19 June 1299, the Bishop of Paderborn himself consecrated the newly-built old town parish church (which is still the parish church today).

The new town of Warburg was founded by Bishop Bernhard IV of Paderborn in 1228. It obtained its own city charter, a market, a town hall and its own parish church. Like the old town it was independent from the start. Both towns became members of the Hanseatic League in 1364 as one parish.

The economic strength required for the early and relatively extensive building activity considering the size of both towns was due to already established manufacturing industries and local and long-distance trading. Economic life was determined by wool and linen weavers, tanners and beer brewers, “canners and potters”, even bell-founders and an influential “Kopmann’s guild”. In addition, the grain trade had always been of importance because the grain surplus from the fertile soils of the Warburger Börde could be sold through the Warburg “trade centre”. Goods from Warburg found their way to Holland in the west and to Hamburg and Lübeck in the north.

Warburg and surroundings

Detail from the Germany map

At the beginning of the 14th century both towns were enclosed by a continuous fortified wall of which four towers and two gates have remained intact.

Both independent towns, the old town and the new town, were constitutionally united as a “one-council” town for the first time by the “Groten Breff (Big Letter)” in 1436. The construction of a new, common town hall was immediately decided. This was to be located on the border between the old and new towns and was to be open on three sides: to the old town, the new town and to the monastery with the monastery church. The master builder cleverly solved this difficult problem with the massive arched hall. The town hall was finally completed 132 years later in 1568.

Picturesque half-timbered buildings of the old town – the earlier the Dominican church “Sancta Maria in Vinea (monastery church)” built at the end of the 12th century, can be seen at the top – Protestant parish church since 1826.

The former town hall of the new town of Warburg was located on the north side of the new town market. It was destroyed in 1760 during the Seven Years War in fighting between the French and the allied English, Prussians and Braunschweig troops. During archaeological excavations in 1984, the well-maintained basement walls and foundations could for the most part be laid bare and documented. According to this documentation this was a building 31.80 m long and 12.60 m broad with outer walls 1.55 m thick. After the construction of a common town hall on the border between the old and new towns, the town hall of the new town was used as a school and “Stadtkeller” serving wine and beer until its destruction.

The former town hall of the old town was a large stone building with three-level gables. The main body of the building consisted of a large basement, a main floor and an upper floor; it had almost the same measurements as the new town town hall (31.57 m x 12.28 m), the walls were of heavy unshaped limestone. According to dendro-chronological measurements, the building dates from 1336. The large hall on the upper floor was used for local council meetings, administrative activities and the town courts – civil and criminal. The room was also available to the public for public and private events, celebrations and also weddings. The town hall lost its function in 1568 when the new common town hall for the old and new towns was completed. However, it retained its function as a festival, trading and storage house. From 1825 on the building was completely altered by a private purchaser. It is still used today (1994).

The town hall of the united old town and new town, built 1568.

View of the entrance to the Protestant church “Sancta Maria in Vinea” through an opening of the arched hall of the common town hall.

The numerous multi-storied half-timbered houses from the 16th century, often adorned with artistic engravings, reflect the self-confidence and prosperity of the Warburg citizens and guilds. There were also, however, setbacks. The plague epidemics from the 14th to the 16th centuries continuously stopped the expansion of prosperity and economic progress of the town. Each epidemic not only caused a drastic reduction in the population but also resulted in a decline of the market due to the reduced demand in the town and surrounding area.

The decline of the town coincided with the start of the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648). Economic decline set in; many buildings were destroyed. In 1621 during the course of the conflict “Tolle Christian” the Duke of Braunschweig appeared at Warburg. The first attempt to take the town was thwarted by the citizens of Warburg. After the fall of Paderborn the regional capital, a second attempt was successful in February 1622 resulting in the ransacking and occupation of the town. In a counter-move imperial troops entered the town. In order to rob the enemy of possibilities for cover, von Blankhart, the imperial commander ordered the cutting down of all trees, hedges and bushes in the town. A memorial stone situated in the former dividing wall behind the monastery church with the inscription “arbores caeae” bears witness to this.

On the whole this war brought great suffering to Warburg through occupation, burning and looting as well as the forced payments to the various occupying forces. The city walls were mostly destroyed, the population was greatly reduced and those remaining drifted into poverty. The numerous deserted buildings and uncultivated fields were also proof that these trying times had robbed the flourishing Hansa city of its splendour and importance. Poverty and misery had replaced economic prosperity. All well-fortified protective buildings were also so badly affected that they were unable to offer appropriate protection and safety to the town and its remaining citizens. Warburg had also completely lost its function as a focal point of the Egge and Weser region.

A ray of hope entered this sad period in 1628 with the establishment of a public secondary school, known today as “Gymnasium Marianum”. This was made possible due to a significant donation by Heinrich Thöne (Thonemann). (See section on “Dr. Heinrich Thöne/Thonemann – founder of the Warburg Gymnasium”).

Both the town of Warburg and the surrounding area were also seriously affected by the Seven Years War from 1756 to 1763 due to enemy occupation, continuous passage of troops and extensive requisitioning. On July 31st 1760, the two opposing groups, the French against the allied English, Prussians and Braunschweig troops, engaged in battle at the gates of Warburg (“the Battle of Warburg”). The English and their allies beat the French and left Warburg to be ransacked so thoroughly that the town and its citizens were scarcely able to recover. The population declined to its lowest ever level of 2000 citizens. It is regrettable that thus the political role of Warburg as the 2nd capital city of the principality of Paderborn was at an end.

In 1813 Warburg was ceded to Prussia, became the main district town and thus won back some of its former importance. A further improvement occurred in 1849 with the connection of the town to the railway network. During the following period Warburg developed into a busy intersection. The population increased in the 19th century to over 5000 and the town expanded beyond the boundaries of its medieval fortifications. Several town gates had to make way for the expansion of the town. In the local municipal reorganization of 1974, Warburg lost its function as a main district town which it had held since 1816 due to the merger of 16 previously independent local authorities (extended district of Warburg); the seat of the district authority was moved to Höxter.

The outstanding importance of the historical town centre today lies for the most part in the preserved former double town structure. Parts of the former town fortifications bear witness to the importance of the town in medieval times and the old town is still partly enclosed by these fortifications today. The view of Warburg from the south is one of the most beautiful in the north-western region. In the Diemel lowland, the old town with its Biermann tower stands out from the slope. Above lies the town on the incline with the former Dominican monastery and the common town hall, on the back of the hill the new town with the gables of the old monastery church and the mound of the former castle grounds.

The town on the slope with the common town hall for the old town and the new town completed in 1568 (top left in picture) based on the constitutional unification of both independent towns on the border between both towns and the opening to three sides through the massive arched hall – left in the background is the new town church – on the top right is the “Gymnasium Marianum” – first secondary school. 1628 due to the endowment of Heinrich Thönen (Thonemann).

The Homes: Half-timbered houses – Stone houses

It is generally well-known that the houses in towns in the Middle Ages were usually half-timber constructions as can be seen in towns where these have been preserved in an exemplary way. Most of the houses in Warburg were also constructed in this way. It was the carpenter, not the mason, who had the most work and the main responsiblity for the building. Certain indications with regard to building techniques can be gained from later constructions where oak beams were put to use a second time. In order to obtain a better understanding of the spatial structure of the houses of that period (14th to 16th century), it is necessary to imagine the social and economic conditions of the time.

The social structure of medieval times was determined by the patriarchal extended family which as an economic community was more pronounced than in later times and comprised in addition to generations of the nuclear family single relatives, servants and other dependant persons. They provided themselves for the most part with food which was usually taken from their own or leased gardens and fields and had to be processed and stored at home. Usually a trade was also practised which also took up considerable room and storage space in the house. Medieval homes must therefore be considered as commercial buildings in which only a small part of the main building was used for residential purposes.

Cellars, the half of which were set deeper, were, as a rule, constructed at the rear of the commercial rooms of the larger houses of that time and were used to store provisions. Examples of these can still be found in Warburg today. Most of these originally had a timber ceiling and only became vaulted in the 15th and 16th century. Cabinet niches with grooves for the insertion of shelves and traces of former sealing caps or cabinet doors can often be found in the walls.

The well-off citizens not only had a stone basement but had also, or instead, a stone rear part of the building on the upper floors. In documents these constructions are referred to as “steyn kamern” (stone rooms). These were also found in other towns and served mainly to protect and provide safe and fire-proof storage of the provisions for the extended household.

The early half-timbered houses were relatively small and modest compared with those of later times or of the present day. There were no ornamental engravings or carvings on the supporting stays. The house framework consisted of high boarded wall props at large intervals from one another connected by continuous scarf-joined bars and cross-struts. The ceiling beams were mortised (“shot”) through the wall props and cross-reinforced by simple lap-jointed brackets. A fireplace was located in the back third of the inside of the house.

In addition to the half-timbered houses (“hüser”) and stone rooms (“steyn kamern”) there were also a number of stone residential buildings in the Warburg old town. These “steynhüser” were specifically mentioned in old documents and were owned mainly by nobility and patricians. Since this upper class acquired its income from feudal tenure, ministerial offices or the employment of servants, a working room (“Deele”) with street access was not necessary. The stone houses were generally accessed from the eaves via the usually large sites and were probably surrounded by several adjacent buildings. The oldest recorded stone house in Warburg is the “Haus zum Stern”, Sternstraße 35, dating from 1340 which serves as a museum and town recording office today. For many decades it had been the private property of the “von Windelen” family and was later used to accommodate the Wormeln nuns after the destruction of the Wormeln convent by “Tolle Christian” in 1622. It was later reconstructed and during the Seven Years War served to accommodate numerous dignitaries. It was acquired by the Rosemeyer family in 1787. Extensive reconstruction took place at this time and the present interior dates from this period. The town of Warburg acquired possession in 1921 which serves as a town recording office and local history museum.

“Haus zum Stern”, Sternstraße 35 in Warburg built in 1340 – renovated and altered – since 1959 town recording office and museum.

In a wave of renovations starting in the second half of the 15th century, numerous dwellings and stone houses in Warburg were replaced by larger and more extensive half-timbered buildings. This was a process which according to latest research also took place in other towns such as Höxter and Lemgo in the late 16th century. The oldest half-timbered residence of this group is the so-called “Eckmänneken” in the old town, Lange Straße 2. The inscription on the storage floor threshold reads: “M ccc LXXI hec. Domus est edificata” (this house was built in the 1471st Year the Lord). This is the oldest dated (half-timbered) house inscription in Westphalia. The existing building is unfortunately only a faithful replica of the original using the old components. The interior does not reflect the first construction. The original house was used by the office of bakers as a meeting place and was probably built and inhabited by the guild master. Three carved “Wecken” (rolls) in the inscription beam and a pretzel can be admired. The two carved figures on the corner-stays facing the market place are not only interesting but also give a vivid impression of 15th century fashion with short belted coats and the gothic-fashioned tights.

The “Eckmänneken” – house in the old town, Lange Str. 2 is the oldest known half-timbered house in Westphalia to be recorded in an inscription. It was constructed in 1471 as a bakers’ guild house – remembered in carved rolls and pretzels – the two carved figures on the corner-stays facing the market place give a vivid impression of 15th century fashion with short belted coats and the gothic-fashioned tights – today a restaurant.

In time the town residences in Warburg underwent gradual change which was at first formal but eventually had an increasing impact on the construction and spatial structure and division. Increasing requirements for presentation of the middle class led to a considerable increase in woodwork adornments with ornaments and banners. Complicated medieval constructions were abandoned in favour of simple floored buildings with mortised bars and stays. The increasing differentiation between household functions and advancement in heating techniques caused a gradual subdivision of the inside of the house whereby the large hallway was reduced to a middle corridor.

The manner of living of the townspeople, eating and drinking was also simpler than we would imagine. The history of “fine table manners” requiring appropriately large and structured rooms is relatively short. Even when taking into account the fact that banquets were a highlight of noble life in medieval times, the prevailing manners of those gatherings would scarcely be regarded as particularly noble or commendable today. Up to the 16th century we still happily plunged our hands into the meat bowl. It was only at the end of the 15th century that the first forks appeared on the table and plates were placed in front of each guest. The decisive turn in the history of fine living emanated from France; especially through the Sun King Louis XIV (1643 to 1715) brought about a change which only very gradually reached wide sections of the populations of the states.

The town’s inhabitants

The inhabitants of Warburg – as in the “Großen Brief” (Big Letter) – were divided into three categories: “Bürger” (citizens), “Pfahlbürger” (without citizenship and the right to settle in the town) and co-inhabitants. Each of these groups had a different legal status. Co-inhabitants were people from outside who had been allowed by the town council to live in the town because their presence or temporarily practised activity promised to be of common benefit to Warburg. These people were obliged to observe the town’s duties and pay dues without, however, enjoying civil rights. These inhabitants of the town were thus denied both the right of membership in a guild or of holding any kind of office.

In the Middle Ages citizens of villages protected by stakes and wickerwork were called “Pfahlbürger” or “Ausbürger” or “Schutzbürger”, i.e. inhabitants living outside the town fortifications in the “suburbs” or also inhabitants from the country who had acquired civil rights in another town. As such people often attempted to avoid their duties as subjects to their previous lord they were often forbidden from entering towns at the instigation of the lords since the 13th Century.

The Pfahlbürger referred to in the Warburg subdivisions did not belong to this category but were important in military terms as representatives of the nobility residing in the neighbourhood or surrounding area who shared civil rights of the town of Warburg due to their need for increased security and the extension of their political influence in the surrounding area. The town, however, did not give these Pfahlbürger passive voting rights.

Only the actual citizens of the town therefore were eligible for the office of councillor.

The group of citizens, however, was not a uniform block; the bourgeoisie was itself subdivided; it represented a continuation of the medieval hierarchical structure of society. Here also were groups in possession of the actual city power, such as self-administration and town jurisdiction, who cut themselves off from society as a whole and like the nobility – claim and possess a leading role with corresponding special rights.

To be more precise: not all citizens of the town of Warburg could become town councillors; “council competency” was restricted to only a certain circle of highly-regarded and affluent families, the so-called patriciate. This phenomenon was most apparent in the existing voting regulations whereby the new council was selected by the old. This excluded any participation by the rest of the citizens. Thus the majority of citizens were unable to influence the fate of the town; control and power lay in the hands of a small rich minority. The council thus became an instrument of the patriciate families, or in other words: the council members were not real representatives of the people. It should not be forgotten here that many citizens – and this has remained so until the present day – are not interested in taking up public office. The experience from this period is that the middle classes, if able to influence the taking up of political office in the town, still tended to leave the top offices in council and administration to the old council family lines and patricians. The reasons were, on the one hand, the extensive political experience of the leading families and, on the other hand, the work and costs involved for the person taking office.

Wealth and prosperity were in the hands of the patriciate, not the mostly impoverished country nobility. The patriciate was generally the lender of money for the nobility all the way up to the Kaiser. The country nobles sought their (well-to-do) wives among the town patriciate.

Entrance to “St Maria im Weinberg” – end of 12th century – Dominican church since 1283 – alteration of chancel in the 1st half of 14th century – ridge turret neo-Gothic 1895 – since 1826 Protestant parish church.

Complete view of the high altar of the Protestant church “St. Maria im Weinberg”. The altar donated for the Dominican church in 1666 was given back its original baroque colour with its careful restoration in 1982/83 – altarpiece depiction “Mary’s entry to Heaven” being carried away by angels.

Functions and importance of the Council (Rat)

The Warburg town council consisted of 12 persons even before the merger of both towns (1436) and these elected a mayor from their midst. A new election took place annually at the beginning of the new year. Only the previous council was eligible to vote. This rule already applied to the old and new towns before the merger.

The “Großen Brief” (Big Letter) of unification of the old and new towns of Warburg in 1436 laid down the regulations for the future common council which were also to apply to the annual renewal of the council. The twelve retiring councillors elected their successors as well as two mayors from their midst, each of whom was to control the seal and chair the council meetings for half a year. One of these should live in the old town the other in the new town. This principle of one town council year and twelve councillors corresponded to general traditions and customs of old and new towns before unification. There were occasional exceptions, also in other towns similar to Warburg, that some council members could be re-elected to the new council. Warburg, however, like Paderborn and Lippstadt, kept to the policy of annual replacement.

Although the council was newly elected each year, its composition however remained relatively constant as council members and mayors often returned to office every two years. Thus these offices were basically held by a small circle of councillors. A large number of patricians were elected councillor or mayor for 10 or 20 or even more years.

The old “Altstädter Rathaus” – a stone building with three-level gables – high cellar floor – built in 1336 as town hall. Festivities hall, shop and storage house – function as town hall 1568 lost due to reconstruction of common town hall for old town and new town – used as restaurant today.

The patriciate in Warburg felt an affinity for the nobility; relationships were often forged through marriage. Frequently mentioned noble and patrician lines during this period were the Geismar, Nabercord, Ordecken, Gerold, von Menne, Thöne/Thonemann, Schlicker, von Höxter, von Steinheim, von Listingen, Reussen, Volmar and Schepers families. Several of these families were interrelated.

The leading councillors were not at all opposed to having tradesmen in their circle. A certain amount of wealth, however, was a precondition; as those holding office had to be in a position to put aside professional activities in favour of the new position since – unlike present times – councillors and mayors did not receive payment or compensation.

In general – as has already been mentioned – the citizens had little or no interest in taking up public office. They obviously felt themselves sufficiently represented in political affairs by the rich, experienced and well-educated council families.

The governing council, however, did not hold exclusive power for the one-year term of office. In certain cases two further committees were involved, the previous council, known as the “Alderat” and 18 “upright men from the locality” who were chosen by the ruling councillors, 9 from the old town and new town respectively. The chairmanship of these committees was held by one of the previous year’s mayors. The precondition for the meeting of this committee was an invitation, or rather summoning, by the sitting council. The council was obliged to summon both committees only when new laws were being passed.

With its twelve council members, Warburg was not unusual and this number was also found in many similar towns and was only exceeded in much larger towns; towns smaller than Warburg only had a fraction of this number.

The complete civil jurisdiction was incumbent upon the town council; the town judges had almost completely lost this to the council. Since the 17th century the council court was also the appeal authority for decisions taken by the town judge.

The Warburg council took efforts for the observation of the law of the first instance (“jus primae instantiae”). This meant that those wishing to become citizens or to take up offices in the town had to promise not to take citizens or Pfahlbürger to a clerical or external court but to the council court in Warburg. The Warburg council also possessed a former sovereign right, that of trade sovereignty. With the unification of both towns in 1436 this right was reconfirmed in the “Großen Brief” (Big Letter) through the freedom to issue guild certificates; Warburg also obtained further former lordly sovereignty rights which were important for economic development such as customs prerogatives, the right to mint coins and the control of markets.

Due to the expanded and firm autonomy the economic development of Warburg continued after the unification of both towns.

During the 15th and 16th centuries the Warburg guilds enjoyed generally secured prosperity which was partly due to their ability to produce surpluses and to invest these profitably, e.g. investment certificates of some trades guilds.

Since the 15th century Warburg council had market control rights which had formerly been under the control of the state sovereign. The council appointed one of its members market master to examine the goods on offer at the market, determine prices and supervise the use of weights and measures. In the event of violations fines were imposed by the council.

Decline of the power of the Council

The provisions of the “Großen Brief” (Big Letter) of 1436 were generally observed by the Warburg council for the old town and new town and lasted until 1667 – i.e. 231 years. Records of council meetings show that the previous council and the local committee were consulted on important occasions and the requirement that one of the two mayors and half of the councillors should be resident in the old and new towns respectively was also adhered to. There was no change either with regard to the number of council members or the two mayors. Council renewal as required in the “Großen Brief” took place annually in the first weeks of January.

The sovereign in Paderborn regarded the extensive power with scepticism; he repeatedly attempted to reduce the sovereignty practised by the towns as well as the position and power of the council. Thus in 1580 in the name of the towns of the principality the Bishop of Paderborn’s new coinage regulations were recognised by Warburg and Paderborn.

In 1662 the Bishop of Paderborn succeeded in regaining control of customs in Warburg. In 1613 intervention in the guild system was also successful; likewise the centralisation of the legal system was pushed ahead in the middle of the century. After many failed attempts the sovereign succeeded in 1667 in administering the final blow to municipal independence by the determination of a new voting system for the council constitution. The impact of the Thirty Years War and the disquiet among the Warbug citizens concerning what they regarded as unfair billeting and contributions made it relatively easy for the sovereign to make the long-desired intervention.

The Paderborn bishop Ferdinand II, who ruled the region from 1661 to 1683, issued the following ordinance:

“Und damit dann auch bei kunfftiger rathswahl der verdacht aller partialität (wohl Parteilichkeit) eingestellt pleiben möge, so thun wir dem bishero gehaltenen modum eligendi (Wahlmodus) … hiermit aus landesfurstlicher macht und gewaltt und auß dazu bewegenden erheblichen ursachen zumathen auffheben.” (“so that the suspicion of partiality in future council elections may be prevented, we are herewith according to princely power, repealing the hitherto applied modum eligendi (electoral mode)”.)

This state legislative ordinance by the bishop in 1667 repealed the existing election system and replaced it with a new one. In a general assembly lots were drawn from the six town Bauerschaften (groups of farmers) to select two electors from each.

These 12 electors had to elect – without receiving instructions – 12 men (no women!) from the citizenry as future councillors. On the following day the 12 selected persons were installed and sworn in by the outgoing council. All records and keys were handed over to the new council. The new councillors elected the two mayors from their midst.

The spirit of that time was indicated by a further sovereign decree:

“Damit es mit diesem eligendi modo so viell aufrichtiger auch gehalten werde, so soll unser zeitlicher Gogräff daselbst als unser spezialiter dazu verordneter Commissarius dieser Bürgermeisterwahl nicht allein, sondern auch dem vorigen actui beywohnen und praesidiren, die per sortem (durch Los) auß der Gemeinheit genohmenen Churmänner auch hiebei kommender Form in ayde und pflichten nehmen” und nach Abschluß des von ihm kontrollierten gesamten Vorgangs noch entscheiden, ob nichts bedenkliches zu beobachten war. (“So that it will be done much more honestly with this electoral mode, our temporal Gogräff himself as our specially decreed commissioner for this task of the mayoral election will not preside alone, but also the previous citizen, and take the electors chosen from the community by lot also in this form under oath and obligation” and on conclusion of the entire process controlled by him will decide whether there was anything dubious to observe.)

This meant that the three electoral procedures were to be monitored and controlled by the state commissioner and that the election required the approval of the sovereign. A municipal constitution formerly based on autonomy was disposed of and the council demoted to a state bureaucratic committee subject to the permanent control by, and subordination to, a state official.

Thus the new regulations were not met with approval by the old, tried and tested Warburg councillor families. A counter-offensive was started with the selection of the electors by clandestinely influencing the lot-drawing process (“corriger la fortune”). These attempts were just as unsuccessful as the official entreaties of the citizens and nobles to the sovereign. The situation deteriorated when the next bishop, Hermann Werner (1683 to 1704) decreed that a state collector was to be installed for both towns thus withdrawing financial sovereignty from the mayor and council. It was only in 1739 that a slight correction was made by Bishop Clemens August (1719 to 1761). The bureaucratic and absolutist regulation remained, however, until after the days of prince-bishops.

Catholic parish church St. Johannes Baptista in Warburg new town (new town church)

Regardless from which direction one approaches Warburg, from the motorway or the Warburg Börde, from Kassel or Paderborn, the first sight is that of the high spire of the new town parish church. This not only shows clearly the position of the Warburg new town on a mountain ridge 60 m above the Diemel valley but also the central position given to the parish church when designing the town. Together with the market place – the town hall of the new town also stood here as indicated by a plaque – it is situated at one of the town’s highest points which rises slightly towards the south.

The reasons for and the timing of construction of the church is connected with the origin of the new town. The new town is first documented as an independent town with a constitutional council in 1239. Bishop Bernhard IV (1227 to 1247) is known as the founder. It is also probable that he initiated the erection of the church. The appearance of the church today goes back to the careful renovation between 1899 and 1908. The spire retrieved its gothic cupola in 1902 as it was shown in copperplate engravings by Braun/Hogenberg in 1581 and Merian in 1647. The high altar in baroque style designed by J.C. Schlaun in 1714 was broken off in 1882 and replaced in 1882 by a neo-gothic stone one designed by the Cologne architect Wiethase. The pictures on the church windows are a qualitative example of historical glasswork. The stone Renaissance pulpit from 1611 depicts the church patron saint John the Baptist in the middle, underneath the field with the coat of arms of the founder by Heinrich Buelicken. The Latin inscription on the pulpit urges: “spread the Word, insistently, whether convenient or inconvenient”. The following are worth seeing: the gothic Pieta from 1370 and Christ in pain from 1500, the late-gothic winged altarpiece “Charvinalter” in the Herz-Jesu Chapel from around 1450 and finally “Baptism of Christ”, a group of figures created by J.C. Schlaun in 1719.

A walk around the church reveals the use of two kinds of building materials; the western parts including the spire and the later added side chapel are of grey and white limestone, the chancel is of red sandstone. Viewed from the market place, the massive 77m high west spire dominates both the architecture of the square and the church building.

The new town parish church in Warburg “St. Johannes Baptista” – the spire retrieved its high gothic cupola in 1902 – complete restoration 1899 – 1908.

The new town parish church (Catholic) – the different building phases are clearly visible.

Epidemics, feuds and town debts cause economic decline

The regular occurrence of epidemics plunged Warburg into long-lasting decline. There were several reasons for this: first the people of the town itself were affected, and the death rate rose immensely; second, with the decrease in population the town lost a large part of its function as a grain market; since there was no demand for grain as a result of the declining population even the business-minded traders were unable to sell their products. This decline also affected the production and sale of textiles. Thirdly, Warburg lost suppliers from the surrounding area, especially the productive Warburger Börde. The epidemics apparently spread from place to place via the trading routes.

There was a further reason: During the 14th and 15th centuries the decline was speeded up by numerous feuds. This was caused by social restructuring processes and the lack of institutional stateliness in the diocese of Paderborn. Added to this was the financial weakness of the town of Warburg; money had to be borrowed on a large scale; the citizens were nevertheless still solvent.

The insecurity in both the old town and new town could only be reduced by improvements to defence capability. After the merger in 1436 work was begun on the expansion and renovation of the walls and towers. The Sack tower was built in 1443 as part of this improvement program. The citizens of Warburg themselves had to play their part in these improvements. Their contributions were both of a financial and material nature; for example, the “schott” a property tax, “perdegeld” (horse money), “bolwerkes” a contribution to defence, work on the town fortifications, “wachte” keeping watch as a neighbourhood or farming community measure as well as certain “duties and responsibilities”.

Frankenturm from 1350 – defence tower in the double wall ring on the north side of Warburg new town (14th century).

From the middle of the 15th century measures were taken first to reschedule and later to pay back the town’s debts. The annual and weekly Warburg markets gradually became more attractive. The exchange rates for Warburg coinage and Rhine golden guilders as well as Münster, Osnabrück and Dortmund gold stamping were determined regularly at the Warburg market from1480.

The Reformation Period

The Reformation and its repercussions also left their mark on Warburg. Although the Warburg council had banned all agitating sermons in its area of jurisdiction and defended the Catholic faith at all opportunities, the meetings in front of the town gates could not be effectively opposed. Due to the public appearance of the new town priest Otto Beckmann who was born in Warburg in 1476, the new doctrine could not be established; Beckmann like Luther, attached great importance to preaching and made significant use of this method of religious revival. He had studied in Leipzig and Wittenberg obtaining the chair for grammar and had known and respected Martin Luther. He accepted the need for Church reform but could not follow Luther in his struggle against the papacy. He was so strongly affected by a demonstration of opponents of the old church during Christmas Mass celebrated on the occasion of his visit to his home town of Warburg in 1522 that he gave up his professorship in Wittenberg in order to be “teacher and reminder of the dear citizens (of Warburg)”. He reminded the citizens that many were Christians in name only and demanded that they attend the Sunday sermons. In order to improve the faith of his hearers he undertook a series of sermons on the seven petitions of the Lord’s Prayer. Using Luther’s example he had the most important prayers read out loud during Sunday mass. He criticised the indifference and half-heartedness of the Christians and concluded that God would punish such indifference with illness, plagues, failed harvests and infant mortality. His activities in Warburg had a great impact due to his constant and decisive advocacy of religious behaviour with the love of God and human respect. The good preacher remained as priest of St. John the Baptist Church in Warburg new town until his death. The fact that reforming ideas stood no chance in Warburg (at this stage) can certainly to a great extent be credited to him.