General information

Armory refers to “that aspectof a herald’s work which is concerned with the marshalling and regulation of coats of arms and other hereditary devices and insignia according to established conventions, practices, and precedents” (Stephen Friar). As such, it may be subdivided into three important aspects:

• theoretical armory which deals with the laws and rules underlying the design of a coat of arms, the right to bear of coat of arms, the history of armory and, finally, the knowledge about the individual devices which, at an earlier age, was identical with the knowledge of persons;

• the practical art of armory which deals with the creation and the design of a coat of arms, its outline or sketch, and the correct armorial representation of all parts and components of a coat of arms, according to established conventions and precedents;

• and, finally, the legal aspects of armory which comprise the various rights to coats of arms and their use, including the right to use a seal, the control of the uniqueness of individual devices, distinctive features, and the titles to given coats of arms.

Historical development of the coat of arms

From their origin to the present day, the history of the coat of arms, of armory and of its respective regulations can be divided into three major periods:

• the armory of the shield (the Origins);

• the so-called ‘living’ armory (the Age of Chivalry);

• and the so-called ‘dead’ armory (the Heraldry of Decadence).

In the course of the 12th century, the shield – which had hitherto been made of more or less valuable material – came to be used for the display of devices and insignia identifying its bearer; however, such individual marks of distinction were not yet hereditary.

From a military point of view, insignia on the shield were a bare necessity, because clearly identifiable signs of an individual helped to make him known on the battle-field, to friend and foe alike. The use of such identifying devices was however still restricted to the shield proper; the heavy and simple battle helmet was not yet supplied with a crest and mantling which were later considered to be necessary components in a full achievement of arms. The repetition of tinctures (colours) of the shield on the helmet can therefore only be regarded as an additional indication of identity.

A renewed influence of the techniques of war and weapons on the development of armory is in evidence towards the end of the 13th century, that is in a period when serious battles and battle games were scarcely distinguishable. These new developments mark the end of the period of the ‘armory of the shield’.

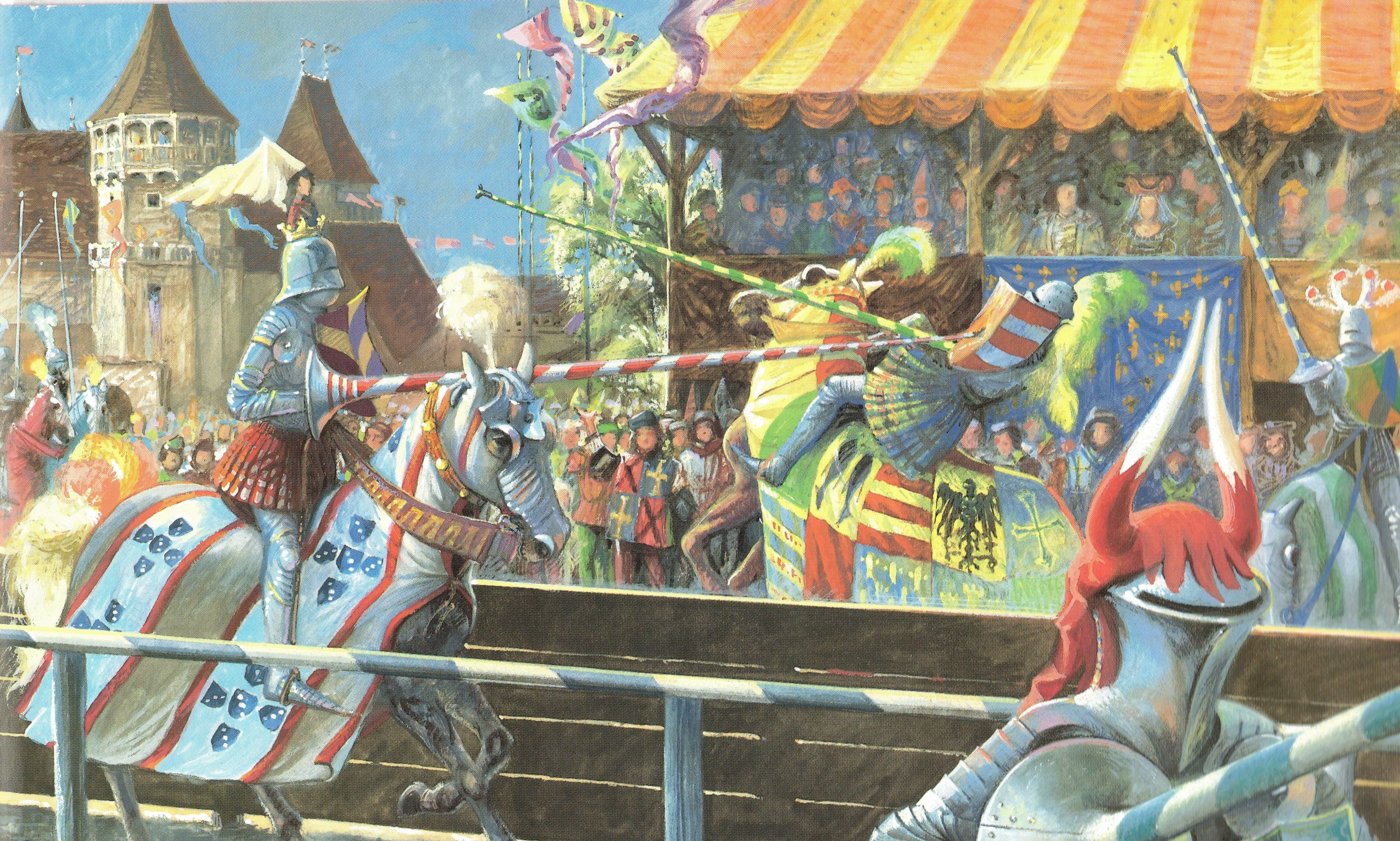

From then on, the coat of arms increasingly gained significance. Originally, a knight may have changed his shield figure several times; it now became a permanent mark of its bearer. From 1200 onwards, it gradually became hereditary, and its function changed from being a mark of personal identity, to becoming the armorial sign of a family; the crest replaced the shield figure as a new and personal mark of the individual knight. These changes signal a new period in the development of armory as an art of its own. The crest will identify the participants of a tournament in the display of helmets which precedes it; at the same time, it serves as evidence of the participant’s eligibility.

From then on, the shield, the helmet, the mantling, and the crest become the essential components of a full armorial achievement. The shield which in former times had mainly served as a protective device, acquired an additional value as part of an overall heraldic design. It is at this point in the development that the period of the so-called ‘living’ armory begins: the heyday of the coat of arms will continue throughout the middle ages, to the beginning of the 16th century. During this period, the bearer of a coat of arms did use their arms in combat and tournaments; in this period, armory came to be considered an essential element of the military class, of standards of military conduct and of the notions of chivalry and chivalric ideals. As part of seals, coats of arms also gained legal significance.

The age of the so-called ‘dead’ armory begins with the invention of firearms. Their introduction led to far-reaching changes in the technique of fighting and the technology of armor; sense and purpose of the chivalric weapons of defence were lost. Eventually tournaments also met their end; thus, the practical use of shields and helmets displaying a coat of arms became extinct. From then on, armory could only hold its own in the use of seals and as a decorative element; it could only stand its ground until arbitrariness and ignorance finally led to decadence and decay; in the end, coats of arms and armory were fossilized into rigid chancery conventions which had lost their original meanings and their original social functions.

The Heralds

Due to their expert knowledge of armory and persons, heralds were particularly suited as servants of kings and magnates; heralds were also responsible for arranging and supervising tournaments. They wore a surcoat (known as “Tappert” in German) which was adorned with the coat of arms of their lords – the heraldic badge and liveries of the English tradition. It was their duty and right to organize the display of helmets which preceded the tournaments; it was their task to check the coat of arms of the participants thoroughly for their correctness; it was their duty to insist on a strict observation of the regulations for the application of tinctures, to reject coats of arms to which there was no right, to decide on the eligibility of participants and, finally, to draw up reports of the tournaments. In the heyday of armory, from the 13th to the beginning of the 16th centuries, the management of ceremonial, the ordering and recording of armorial devices used on seals, at tournaments and in warfare lay all in the hands of the heralds; they devised the conventions and terminology of armory, and they greatly contributed to its systematic development.

Once we pass the beginning of the 16th century, the duties and rights of the individual heralds were increasingly transferred to heraldic institutions so that the heralds gradually lost their significance and disappeared in the end.

(We would like to take this opportunity to express our thanks to Professor Wilhelm Busse of the Chair of Medieval English Literature and Historical Linguistics at the University of Düsseldorf in Germany for his kind support in translating this text and possible supplements.)