The monastic village of Scherfede

Scherfede – general overview

Scherfede is about 10 km north-west of Warburg; since the administrative reform of 1975 the village belongs to the town of Warburg. Already in 850 the village “Scerva” was mentioned as a self-contained settlement in the property register of the imperial abbey of Corvey. The stone box grave between Scherfede and Rimbeck, the sacrificial altars in Hardehausen Forest, north-east of Scherfede, the Gaulskopf and the Leuchtenberg as a location for walled castles and fortified hideouts during the Saxon War (722 to 804) indicate the early historical development of this area. As one of the early monastic villages (see “The monastery in Hardehausen”) Scherfede was closely connected in its development with Hardehausen monastery up to secularisation in 1803. During the Thirty Years War, especially in the years 1642/43, Scherfede was up to 80% destroyed and was hardly inhabited.

Scherfede 1992 at the south of the Egge mountain range, near the Kassel-Dortmund motorway, at the intersection of the B 68, B 252 and B 7. The first documented mention was around 850. In 1642/43 75% was destroyed. Until World War Two a junction for railway lines from north to south, as well as east to west. Next to the core town of Warburg the second main industrial focus with service providers and numerous retailers, handicraft firms and industrial businesses ensuring the supply of the neighbouring villages.

For centuries Scherfede was a place whose inhabitants were in farming. The first successes in economic development were achieved in the 17th Century with the construction of a forge in Hammerbachtal. This “Hammer”, which operated into the 19th Century, processed the neighbouring Waldeck pig-iron to forging steel. However a visible upturn first followed the foundation of the wool factory (1863) and the completion of the railway line Warburg – Scherfede in 1873. Industry, handicrafts and trade bloomed in the up till then purely agricultural village. Small industry and wood processing firms settled down beside wool factories. With the growth of the population handicraft firms like bakers, shoemakers, joiners, butchers, tailors, dyers, millers and masons were added. Trade, business, handicrafts and small industry make Scherfede today (1994) a considerable economic factor within the big community of Warburg. Production accounts for 60% of jobs.

Also the favourable traffic situation encouraged the settlement of small and also big handicrafts and business firms. For in Scherfede the federal highways B 7, B 68 and B 252 intersect. A slip road leads to the Kassel-Dortmund motorway nearby.

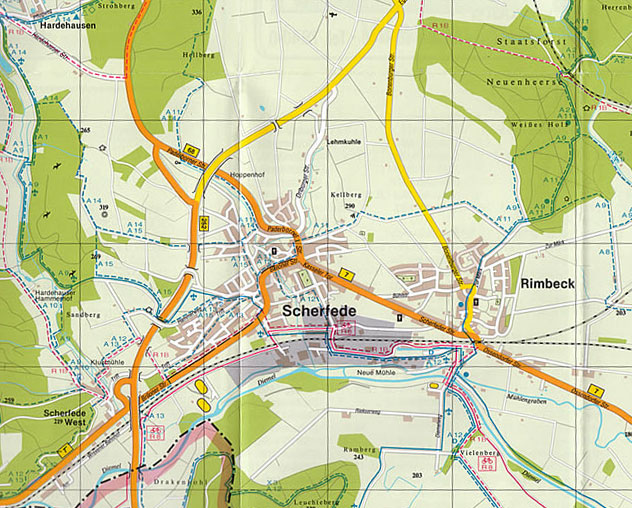

An overview of Scherfede, Hardehausen and Rimbeck

A section of the map of the district 1:50,000

The parish of Scherfede is, as can be deduced from the patronage of St. Vincenz Levita, very old and already had a church in the 10th Century.

A church in Scherfede was documented in 1231; it was rebuilt in the 17th Century and had to be pulled down due to dilapidation in 1857. The present parish church, built in neo-gothic style and consecrated by Bishop Konrad Martin from Paderborn on 26th April 1863, stands on the same spot.

Also at the end of World War Two Scherfede was the scene of combat. As American troops from the south and west occupied Diemeltal, German soldiers tried to defend Scherfede. On Good Friday, 30th March 1945, the Americans opened fire and fired on the village also over Easter. As a result, 19 houses burnt down, numerous buildings were badly damaged. There was also a direct hit on the church on Easter Sunday. And worse: several people from Scherfede died, numerous others were wounded, 40 German soldiers fell in this combat.

Did any of those fighting think of the history of previous wars and devastation, of the want, privation and misery accompanying the events of war and at this time, when the war was long lost, draw conclusions?

The wool factory in Scherfede in 1863

Today the major part of the Scherfede boundary is in the nature park “Eggegebirge – Südlicher Teutoburger Wald”. In 1974 a 2.4-hectare recreational lake was created in Hammerbachtal. This attracts numerous visitors on account of the pens for bison, wild horses and pigs. A 70 km network of hiking paths with large deciduous and coniferous woods and cliffs, fish-ponds and newly-laid humid biotopes completes the attractive surroundings.

Scherfede in the 15th and 16th Centuries

From 1435 Hardehausen monastery was lord and master of its monastic villages, including Scherfede and Rimbeck. There it exercised ownership and lower legal jurisdiction. Sovereign at this time was the royal bishop of Paderborn. The bonded peasant had no title to the land he worked, but the unlimited right of use which was hereditary and was transferred to his descendants. He was also able to purchase land with the approval of the monastery, however not more than 60 acres (1 acre = 0.25 hectares). For the right of use the peasant had to pay an annual fee, the so-called “Zehnten”, i.e. at harvest time every tenth bundle of grain or flax had to be handed over. Besides this certain unpaid manual work and unpaid horse and cart work had to be done and certain payments in kind like eggs or poultry had to be brought to the delivery point at stipulated times. However this inherited subservience should not be seen too negatively; both sides strove for a good relationship to each other, both peasants and monastery. It must also be kept in mind that the monastery had to ensure the safety of its villages in the event of attacks in feuds and times of war. In Scherfede the fees were paid in the main yard of the monastery, later after about 1700 in the “Zehntscheune”. The “Zehntscheune” in Scherfede was built in 1695 under Abbot Stephan Overgaer. A coat of arms under the entrance at the south side of the historical building – a heart from which three roses grow – still reminds us today of this important priest and member of the order. The “Zehntscheune” was fundamentally renovated in 1977 and serves today as a parish home of ecclesiastical and other institutions and clubs as places of education and meeting.

The parish church built in the neo-gothic style on the same place as the church first documented in 1231 and torn down in 1857 – was consecrated by Bishop Konrad Martin on 26.4.1863. The stream “Springbache” in the foreground.

The standard of living of the agricultural population cannot be compared to ours today. The home – or rather dwelling – was simple, often wretched and unhealthy; clothes and shoes were as a rule handmade. Nourishment was simple and with little variety; staple foods were milk, legumes, little meat, and bread. Root crops, turnips and (fodder) beet were unknown; only the swede which mainly served human nourishment was cultivated. The potato was not yet grown; it spread in the second half of the 16th Century through conquest in Europe, was first planted in Spain as a garden plant, cultivation in Germany was decisively promoted by Friedrich the Great (1740 to 1786), but first around 1850 was planted to a great extent and achieved great significance as a basic food.

Cows were kept as draught animals rather than as dairy cows. At that time the keeping of livestock was still very unprofitable. The stock of cattle on a farm depended on the size and on the farmer‘s own requirements for milk and dairy products; milk consumption was certainly considerably greater than today, as milk-foods were eaten every day. A dairy cow yielded no more than four measures = 6 – 7 litres of milk, as can be seen from the Hardehausen files. If the little hay was used up, the cattle had to starve in winter with straw.

Keeping bees was carried on to an extent which is hard to understand in the present day. There was an apiary on almost every farm with mostly 8 to 12 bee families in straw baskets; yields were certainly much higher than today due to the favourable surroundings. The scope was so big because for one honey was the only sweetener, and on the other hand, every house in Scherfede had to pay the monastery a wax fee.

Agricultural land gave a low yield as stable manure was available only to a very limited degree and fertiliser was invented about 1800 by Albrecht Thaer (1752 to 1828). The three-field system which was customary at the time – a third summer grain, a third wintercrops and a third fallow land – and the “Almende” meadows used by all in common made the individual farmers very dependent on the community in the cultivation of their land.

The farmers lived in long-hall houses, occasionally in cross-hall houses; humans, livestock and harvest were under one roof. The livestock was accommodated on both sides of the hall.

The “Zehntscheune in Scherfede built by Stephan Overgaer, the monastery Abbot, in 1695 – in 1977 fundamentally renovated – serves as a parish house and as a place of meeting and education.

Zehntscheune in Scherfede, East entrance

The coat of arms of the monastery Abbot Stephan Overgaer, the builder, at the south entrance of the Zehntscheune in Scherfede (a heart with three roses).

The housing space and the kitchen were in the back part of the house. The stables and the gateway could be watched from the kitchen (in the case of the long-hall house). The roofs were covered with straw. Chimneys were still unknown so that the smoke from the open fireplace was led over the barn-floor; the individual parts of the pig hung in the smoke. Lighting material, wax candles and rape-oil lamps, were used sparingly. The beds were spilled straw or a straw mattress and a heavy feather-pillow eiderdown.

Every family grew flax, made this into linen which served as a material for bed clothes, underwear and smocks. Otherwise, a lot of garments were made of wool.

Life was simple and modest; and nevertheless the farmer felt himself secure and sheltered with his family under the rule of the monastery and satisfied in his natural bonds, even happy and grateful when the Lord God blessed his work. In the event of failed harvests, Hardehausen monastery helped out with seeds and bread grain from its rich stores. Timber was also handed over free of charge from the great monastery forests.

It has been reported that the monastery had a schoolmaster teach the youth in the three R‘s and singing; so it was noticed that in the certificates the number of those who could not write became lower and lower after 1500. Finally the help of the monastery in improving agricultural cultivation methods and in fruit growing can also be mentioned; the monastery promoted not only the eternal welfare but also the temporal welfare of those people entrusted to it to the best of its power. A good Christian attitude!

The political administration of Scherfede in these years before and after the Thirty Years War was carried out by the “council of five”, which consisted of the judge of Scherfede (Johann Thonemann held the office of judge in Scherfede for any years), the head farmer and the first, second and third superintendents, persons appointed by the monastery and instructed in their tasks. The judge was the actual leader of the community, the head farmer regulated the crop rotation of the three-field system, the pasture management on the meadows and the sequence of unpaid manual work and unpaid horse and cart work, while the three superintendents served as advisers to both. Certainly with such an order self-administration cannot be spoken about. The “council of five” bore more an executive rather than a legislative character in the parlance of today.

In 1430 the monastery succeeded in getting the right from the bishop of Paderborn to fortify Scherfede on account of the on-going attacks and feuds. Between Egge and Diemel a land defence consisting of wall and ditches was built by hand and team duties of all those belonging to the monastery. On top of the wall dense beech groves were planted, whose heads were later chopped off and whose branches were woven together into a sturdy hedge. In addition brambles, wild roses and blackberry creepers were planted, so that an effective defence came into being. A watchtower was added, which had to be manned by day and night in times of feuds. The guard had to announce an approaching danger by a signal-light. In 1437 Rimbeck was likewise enclosed.

The people of Scherfede remained true to the old faith

The Reformation also brought tension and disquiet to Scherfede. As Graf von Waldeck, Bishop of Paderborn, converted to the new teaching and demanded this also for the inhabitants of his area according to the ruling principle “Cuius regio, eius religo”, more and more people from Scherfede made their way to Rhode, about 7 kilometres south of Scherfede, in order to listen to the “new preacher”. As the monastery monks in Hardehausen remained true to the old faith, they tried together with the parish priest of Scherfede to warn their “sheep” to attend Sunday mass in Scherfede. It is reported that what the spiritual gentlemen could not do, a man from the people managed. The following happened on a Sunday morning as the citizens of Scherfede were again on their way to Rhode in large numbers: in a narrow “pasture” a shout of “halt” rang out. The said man, worried, from the people stepped in the way and implored with loud and beseeching voice his brothers and sisters from Scherfede to remain faithful to the church of the fathers and the generations before them, to keep the faith passed down to them and to pass it on for the good of the children as well as not to break the baptismal vows. His rousing words were so successful that all vowed their faith aloud, turned back and returned immediately to the old church. The parish priest had a wooden cross with body put up on the place as an expression of thanks to God. Every year the Markus procession goes from the church of Scherfede to “Weltkes-Kreuz” (the owner of the land at the time: Weltkes).

Scherfede in the Thirty Years War

First of all Scherfede was spared at the beginning of the Thirty Years War, however it was even more terrible in the following years. It began in winter 1621/22, as Herzog Christian von Braunschweig, called the “Tolle Christian”, invaded the royal bishopric and attacked Warburg which was defended by the Kurkölnisch soldiers. The negotiations between the two warring parties resulted in agreement on a sum of 145,000 Taler for withdrawal, failing which the whole area would be destroyed and “all farmers would be cut down”. While the demanded forced contribution was being collected, the unrestrained army ravaged in a terrible way. Burnt letters (letters burnt at the corners with an inscription in fire and blood) were handed over to the villagers. The intimidated inhabitants, also of Scherfede, gave up all provisions, money and valuables, only to save their bare lives and the roofs over their heads. Also the neighbouring troops from Hesse made destructive raids into the Paderborn territory again and again. From August 1633 to May 1646 Swedes under General Baudissin with several regiments were in Warburger Land. Some troop or other was always plundering through the villages around Warburg. 1642 and 1643 were catastrophic, unlucky years for Scherfede. The following statistic is a result of the terrible destruction of these awful war years: “Of all the houses in Scherfede at the time (1643) _ were burnt down and destroyed; from more than a hundred families, 33 were still there in 1643; only 18 farms were still there with a limited function. There were still five horses and 78 head of cattle, 20 of which were cows.” Sheep-breeding which was in full bloom was totally destroyed. About 30 houses (dwelling houses and out-buildings) still stood, about the others it was said: “everything knocked down, everything burnt, devastated and spoiled.”

Johann Thonemann‘s family was also badly affected; the statistics show: “Johann Thonemann 2 houses burnt”.

Now that there was a shortage of every wagon and agricultural implement, also draught animals, those remaining in the village did not think of cultivating their fields anymore also with a view to the fact that the next day or the day after new requisitions or destruction would take place. The debts of the 33 families still remaining according to the register amounted to 2,400 Taler, a big debt if a comparison is made to a good horse that cost 10 Taler at the time. The homeless and totally destitute inhabitants tramped about looking for the urgently needed food on the land around or in order to be able to survive at all, joined up with passing troops, with whom they just as unrestrainedly lived and plundered.

The number of lives these evil years claimed from the small village of Scherfede is not known. That many of the mercenaries and bandits died in the village can be concluded from the findings of bones and war weapons made during the excavations for the building of the school.

How terrible individual years of the Thirty Years War could be for every citizen can be seen from a report of Pfarrer Wahle: “In 1638 the Götz regiments caused such havoc in Wrexen (about 3 km south-west of Scherfede) with excessive drinking of spirits and beer, blackmail, rotting of fruit and shameful whoring, the like of which had never been seen here. On New Year‘s Day 1640 the Stadtbergischen mounted and on foot attacked Werthen (about 5 km south-east of Scherfede), took all the livestock, stripped the people of clothes and shoes, took all provisions. While withdrawing they attacked Wrexen, caught 13 cows and innumerable goats and scorched like in Wethen.”

It is clear that the crudeness and licentiousness of the soldiers, mercenaries and the vagabond groups transferred to the remaining farmers in the defence from hostilities and the protection of family members as well as of house, livestock and food.

Added to all the terrible events of war was the permanent companion of this fury of war, the “black death”, the plague (a pestilence which mostly led to death in earlier times) and small-pox (pox, a contagious and dangerous pestilence – mortality of about 30% of those affected in the case of medium seriousness).

The monastery of Scherfede at the turn of the century

Hardehausen monastery was also badly affected by the war; it could not guarantee the safety and protection of the villages any more. In a report from 1632 it is said that “the monks wandered homeless in the country”.

At the end of the war in 1648 the convent consisted of six monks and novices.

After thirty years the word peace rang out in 1648. Thirty years of slaughter, of burning, of plundering, of devastation and of diseases. Two thirds, the elite of the population, were killed. What survived was broken, degenerated; a “whiff of decay” had spread over Germany. If a nation becomes mad in its own language and attitude like the Germans at that time, it is an indication that they have been attacked to the core. The descriptions of misery of that time sound horrible.” (Dr. v. Weiß)

Scherfede after the war

At the end of the war Scherfede had only about 200 inhabitants in 35 houses; they were farmers almost without exception. “The farmers Thonemann, Lossen, Fleigen, Wiemers and Locken had the biggest property”. Each had over 60 acres.

After the long war there was a decisive change in property conditions. Whereas in the time before the war, especially in the hey-day of Hardehausen, the monastery invested the farmers with the lands, after the war the lack of serving brothers or other temporary workers in the monastery forced them to give up working themselves in the monastery villages, also in Scherfede, and to give the landed property to the farmers on lease. The on-going financial embarrassment of the monastery gradually allowed for a fundamental change: the farmers were able to buy the land as their own property. Owing to the constant shortage of money on the part of the monastery great use was made of this opportunity. Also commercial life in Scherfede became significant again after the war. A previously successful shop for commercial products traded in handicraft products. Also the production of potash (Calcium carbonate K2CO3 – needed for the production of soap and glass – was won by extracting vegetable ash with water and evaporating these solutions in pots) increased demonstrably in Scherfede. Forging concerned itself again with the production of agricultural implements and making horseshoes and wagon fittings. Shoemakers and tailors used to work at that time in the contractor‘s house; they mostly got value in kind as well as food in payment, also often work in a team for the fields they cultivated for themselves.

Gasthof Knepper (today, 1994, Luis)

There were not yet butchers and bakers, only the slaughterers who went into the individual houses to slaughter and process the livestock. Most families baked bread in their own ovens, on the shelf outside the house in the garden. The cartwright made wagons to order, but also bedsteads and other household effects. The midwife was held in high esteem in the village; besides her task as a midwife, she was called on for advice and as a nurse in the case of all serious illnesses. In the parish registers beside the record of her death the number of births she assisted in was also noted.

An insight into family conditions at the time can be got from the parish registers of Scherfede parish, which begin in 1640.

Baptised were:

1640 3 children

1644 20 children

1650 33 children

1660 45 children

1670 53 children

Died:

1640 8 people

1641 25 people

1648 6 people

1650 13 people

1660 17 people

Twelve years after the end of the war, in 1660, the figures show a regular, gradual increase. Life took a normal course once more. However, child mortality was noticeably high in these years. So among 17 deaths in Scherfede were eight children, in 1676 from 61 deaths in the three monastery villages even 35 children. Pestilence, especially small-pox, was responsible for this.

The inscription above the door of the house at Briloner Str. 38 (present owner, 2001, Margarete Ploeger) runs:

BERHARDVS SCHEISERS VND SEINE EFRAU ELISABEHA SCHWIGARDI HABEN AUF GOT SÜR TRAUERT UND DIESES HAUS GEBAUT IM JAHRE ANNO 1798

Well-ordered circumstances arose again in Scherfede towards the end of the 17th Century, as the industrious and assertive Westphalian spirit again prevailed.

The spelling and expression three hundred years ago is of interest. It deviated greatly from that of today. An excerpt from the Scherfede treasurer‘s register of 1717 serves as an example of the spelling and expression. “Aredt tohnemann” was involved:

“Anno 1717 drei May Undt Nachfolgenden wochen Undt tagen subReverendissino ac Amplissimo Dno. Laurentio Kremper Abbato hardehusano, sind die in der Scherfedeschen feldmark liegende ländereye wiesen Undt gahrten Von Johannes Boden, Landmesteren aus pickelsheimb quodam camerario daselbst dessen Ruthenschläger gewesen, Undt vom Abt erstlich beeydigt worden, Aredt tohnemann Undt Conrad riesen so gemessen, Undt zu register gebracht worden, Von dem Richter, Burgemeister, Vorsteher Undt ältesten aber aus der Gemeinheit, zur Schatzung gesetzt wie es Vor Undt allezeit gewesen:”

According to the register of 1717, next to Johann Möller and Ricus Biggen, Johann Thonemann had the biggest property in Scherfede, 65 acres. Only the owners of at least 30 acres of land were to be seen as independent farmers. The plots were not yet recorded and laid down for the land register, but were registered by specification of the neighbouring plots.

The harvested corn was very difficult to clean; the great amount of weed soiled not only the fields, but also influenced the taste of the bread. Farm tools were extremely primitive when compared to those of today. An average harvest yielded in the case of average arable land for rye and barley about 5 bushels (= 200 kg), for oats about 6 bushels. The prices for oats, rye and barley varied between 10 and 18 silver ten-pfennig pieces per bushel (40 kg); 8 to 15 Taler was paid for an acre of arable land according to the quality of the soil.

The inscription above the door of the house at Briloner Str. 23 (present owner, 2001, Ferdinand Döring) runs:

GOT SEY DER BESCHÜTZER UND SEGNE DEN BESITZER JOSEPH DÖRING · UND SEINE MUTTER HABEN AUF GOT VERTRAUT UND DIESES HAUS GEBAUET. ANNO 1811

Noticeable when looking at the conditions of ownership is the frequent change of owner in the time between 1717 and 1790. In this period only seven farms remained in the old ownership; presumably a consequence of the Seven Years War, which claimed many victims and made one or the other farmer who had become poor move.

In the spring of 1758 troops passed through Scherfede and Rimbeck almost every day; a regiment of Anglo-German troops was quartered in Warburg and in the villages of Rimbeck, Ossendorf and Scherfede from October 1758 to Easter 1759. On 31st July 1760 there was a battle in the Scherfede area between the English and French troops. The French had to retreat; a massacre and slaughter began. The result: 3000 dead and injured covered the battlefield.

In the years that followed the Diemel formed the border. Scherfede and Rimbeck suffered from the constant movements of troops and plundering. As the troop units needed lots of firewood, the near woods were cleared, fences and stables were pulled down and burnt. Indebtedness of the farmers became widespread, many were forced to sell their property as a result.