Düsseldorf – My Home Town

Düsseldorf – capital of the federal state North Rhine-Westphalia – is situated on both sides of the Rhine at the foothills of the “Bergische Land” in the terraced landscape of the “Niederrhein” – 38 metres above sea level.

The early years

The settlement of Düsseldorf (village where the small river Düssel flows into the Rhine) was first mentioned in 1135 and granted the status of a town by Count Adolf von Berg in 1288.

During the reign of Count Wilhelm of the dynasty Jülich (1360 – 1408) the town expanded remarkably. In 1371 it was given official authority in all matters of jurisdiction. After the count had been given the title of duke in 1380, the sovereigns gradually transferred their residence to Düsseldorf. Jülich, Kleve, Berg, Mark and Ravensberg were joined under the rule of the dukes of Kleve in 1511. Düsseldorf became the capital and acquired a high level of prosperity, especially during the reign of Duke Wilhelm der Reiche (1539 – 1592).

When he died in 1609 without leaving any children Brandenburg and Pfalz-Neuburg were able to stand their ground in the disputes over the succession between Jülich and Kleve. In the “Vertrag von Xanten“ (contract of Xanten) (1614) Jülich, Berg and Düsseldorf were allocated to Pfalz-Neuburg.

The dukes of Pfalz-Neuburg also had their residence in Düsseldorf. By pursuing a policy of neutrality Duke Wolfgang Wilhelm (1614 – 1653) succeeded in protecting the town from major damage during the Thirty Years‘ War (1618 – 1648). The dukes promoted the expansion of the town and its fortification.

Jan Wellem

The reign of the popular Johann Wilhelm (1679 – 1716), called Jan Wellem, had enormous beneficial effects.

His perspicacious measures attracted a lot of craftsmen, merchants and artists. Some of them only stayed for a while but quite a few also settled down and bought houses or received them from the elector as a gift. For his collection of paintings Jan Wellem had a special gallery built from 1709 to 1714, which was a separate building but connected to the palace. This collection, which also comprised quite a number of paintings by Rubens, was transferred to Munich in 1805 where it later became the basis of the “Alte Pinakothek”.

The well-known equestrian statue in front of the city hall at the market place was created by Grupello from 1703 to 1711 and shows the Elector Jan Wellem in all his splendour on a marble pedestal.

After Johann Wilhelm’s death on 8.6.1716 his brother, the Elector Carl Philipp, moved the seat of the court to Mannheim and entrusted his officials with clearing out the courtly household, a fact which was a serious setback for Düsseldorf.

Only under the reign of the Elector Karl Theodor von der Pfalz (1742 – 1799) the town flourished once again. In the Seven Years‘ War – after a bombardment by General Wangenheim’s troops – Düsseldorf was taken in 1758.

Karl Theodor completed the collection of paintings that Jan Wellem had begun and appointed the painter Lambert Krahe as the director of the gallery. In 1777 Krahe founded the academy for painters and sculptors and the sovereign took on the aegis which was the beginning of the famous academy of arts.

In 1787 the spacious “Karlstadt” was laid out. In Pempelfort, situated outside the town gates, the country house of the brothers Jacobi became a meeting place for German intellectuals. Wieland, Humboldt, Herder and Goethe stayed there.

At the end of the 18th century the country house of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (* 1743, † 1819) and his brother Johann Georg became a centre of German intellectual life.

Düsseldorf im 19. Jahrhundert

In 1799 Karl Theodor died without descendants. His successor, Maximilian Joseph von der Pfalz-Birkenfeld-Zweibrücken, had to hand Berg over to Napoleon in 1806 so that Düsseldorf became the capital of the Grand Duchy of Berg. In 1808 Napoleon took over the rule acting as guardian of his nephew Louis Napoleon. When Napoleon stayed in Düsseldorf in 1811 he gave the grounds of the former fortification to the town as a gift – thus making its development to a garden city possible.

After Düsseldorf had been incorporated into Prussia (1815) it became the seat of the head of government and the provincial state parliament in 1824. In 1819 Peter Cornelius became the director of the academy of arts, now called “Königliche Kunstakademie zu Düsseldorf“. But only after his successor, Wilhelm von Schadow, had taken up this position in the autumn of 1826 the academy gained its eminent importance. Among Schadow‘s students were e.g. Theodor Hildebrandt, Karl Friedrich Lessing, Johann Wilhelm Schirmer and Johann Peter Hasenclever who established the international reputation of the “Düsseldorfer Malerschule“. Their works were dominated by landscape and genre paintings, the high quality of which was purely based on artistic inspiration due to lack of conspicuous local subjects.

The academy of arts with its symmetrical lay-out was built in 1879 according to plans of the architect Hermann Riffart. One of the most interesting features of its magnificent facade is the frieze that runs along the east, north and south side of the building with the names of 62 artists from various epochs. In 1896 Prof. Adolf Schill completed the architectural decoration of the building. The ceiling paintings are by Peter Janssen, one of the directors of the academy.

Beginning in 1831 a brisk goods and loading traffic developed at the river dockyard in front of the old palace. Five years later the shareholder company “Dampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft für den Nieder- und Mittelrhein“ was established – one of the first companies in Düsseldorf organised according to modern principles. A chamber of commerce was founded and a pontoon bridge served as the first steady connection to the area on the left side of the river.

In 1838 the first railway-line of the “Rheinprovinz” connected Düsseldorf with the already fully developed industrial region of the “Bergische Land”. When the railway-line Düsseldorf – Erkrath was opened the trains had to be pulled uphill by stationary steam engines. Only seven years later a second railway-line connected Düsseldorf with Cologne and – via the “Ruhrgebiet” – even with Berlin.

Gas lighting illuminated the streets and places of the town since the 1840s.

The “Departementverfassung” – still dating from the time of Napoleon – was replaced by the local code in 1845. More and more certain reservations concerning the Prussian rule were coming to light. The Catholic population feared the increasing political influence of Protestantism and was highly suspicious of the Prussian militarism. This anti-Prussian atmosphere was fuelled by the bad economic situation which mainly affected the working classes in the early days of capitalism.

In the first months of 1848 the revolutionary movement – originating in France – reached Düsseldorf. As one of the first groups some of the artists headed by Ludwig von Milewski joined the revolutionaries. Demands for freedom of the press and the establishment of trials by jury were voiced; Lorenz Cantador organized a militia. On 7th May 1848, shortly after the elections to the “Frankfurter Nationalversammlung”, Mayor Josef von Fuchsius resigned because he did not feel up to the difficult situation any longer.

On 14.5. during the visit of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV to Düsseldorf a public scandal occurred: While the Prussian monarch was riding through the town the outraged population shouted insults and threw horse droppings at him.

After the failure of the Frankfurter Nationalversammlung and bloody barricade-fightings the democratic movement in Düsseldorf was finally put down by Prussian troops. The artist von Milewski was among the dead.

“Ratinger Tor” – built in classical style by Adolph von Vagedes between 1811 and 1814 – one of the most beautiful architectural testimonies of this time in Düsseldorf.

With the exhibition ”Provinzial-Gewerbeausstellung für das Rheinland und Westfalen“ in 1852 Düsseldorf – located in the centre of the industrial region comprising the towns Mönchengladbach/Krefeld, the “Bergische Land” and the “Ruhrgebiet” – had the first opportunity to present itself as a place for exhibitions and trade fairs. Belgian industrialists became aware of the town as a promising economic location and in the same year the first iron-processing enterprises were set up.

After prolonged negotiations with the Prussian building authorities headed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel plans for the expansion of the town to the north and south were authorized on 3.7.1854. For Düsseldorf this date marked the beginning of a fast development from provincial capital to a town of industry and commerce.

From then on the first administrations of industrial enterprises and associations were transferred to Düsseldorf. The further completion of traffic connections together with the proximity to the “Ruhrgebiet” and the high quality of life made Düsseldorf very attractive so that it also became more and more interesting as a location for banks, e.g. the banking house Trinkaus.

The entrepreneurs aimed at developing Düsseldorf into a metropolis of the regional industry by means of mergers and the foundation of interest groups. A central commercial stock exchange was established. From 1860 on it traded securities of the first companies which had been converted into public limited companies.

The so-called “Dreiklassenwahlrecht” – in force until 1918 – divided the population entitled to vote into three groups according to their taxation. At the top were the representatives of the nobility, wealthy merchants, bankers, factory owners, high-ranking army officers and officials. The second class comprised physicians, lawyers, middle-class officials and old-established merchants, followed by members of the lower middle-classes: workmen, innkeepers and tradesmen. In the town council the number of representatives of the first class (only 4% of those entitled to vote) was up to 20 times higher than that of the mostly Catholic representatives of the two other classes. The members of the so-called „fourth class“, the majority of the population, had neither the right to vote nor the right to stand as a candidate in the elections.

The right to vote was granted only to males having reached the age of 25, living in the municipality for more than one year and possessing either land or having a minimum annual income of 600 to 800 “Taler”.

Due to shifts in income caused by rising profits as a result of the industrialization the old-established “Biedermeier” bourgeoisie slowly lost its influence in the municipal administration and institutions to liberal-Protestant entrepreneurs and financiers. Their thinking was characterised by economical rationalism and their attitude to the progressive Prussian state much more approving than that of the conservative Catholic merchants.

In December 1875 Ludwig Hammers resigned from his post as mayor after 25 years. Two months later Friedrich Wilhelm Becker became the first Protestant mayor of Düsseldorf. These political conditions served as the basis for the future development of industry and commerce.

One of the oldest lanes in the old town:

Bäckergasse

The beginnings of the modern city

In 1882/83 Düsseldorf had become a city with a population of 100,000. The third expansion plan of the 19th century – the so-called “Sübben-Plan” – was presented in 1884. The size of the area to be developed had increased sevenfold compared to the plan of 1854. The two railway-lines that hindered the development of the city were combined into one. A new central (passenger) station was opened in 1891 and replaced the old stations which had been closed down.

On the initiative of some industrialists the “Oberkasseler Brücke” was built as the first road bridge from 1896 to 1898. The “Rheinische Bahngesellschaft” (founded in 1895) headed by Heinrich Lueg was not only responsible for the construction and maintenance of the electric railway-line from Düsseldorf to Krefeld (the first railway-line in Europe with express trains) but also for the development of a new part of the city: the “Rheinische Bahngesellschaft” bought the entire land in Oberkassel on the left bank of the river and developed this area into an exclusive residential area for the middle classes.

The step into the 20th century is closely associated with the era Wilhelm Marx, named after that legendary mayor (1898 – 1910). The first high-rise building of the city (1922 – 1924) was also called after him. At the beginning of his term Düsseldorf had a population of 200,000 and at the end of his term it had 360,000 inhabitants.

Marx used the ambition and the demands of the dominating social forces – nearly all industrialists were city councillors (Poensgen, Haniel, Bagel, Lueg, Schieß and others) – for promoting the prosperity and importance of the city. During this period Düsseldorf became the centre of trade associations, trusts, administrations and banks and was called „desk of the Ruhrgebiet“.

Mayor Wilhelm Marx – Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf.

The “Industrie-, Gewerbe- und Kunstausstellung” in 1902 was a milestone in the development of the city and exceeded all expectations. This exhibition had 160 different buildings, about 2500 exhibitors and five million visitors – among them were the Emperor Wilhelm II, the Crown Prince of Siam, the brother of the Japanese emperor, nearly all of the German princes and also numerous ministers from home and abroad. The “Parkhotel” at Corneliusplatz was especially built as an exhibition hotel for upmarket tastes. The “Kunstpalast” was later given to the artists as a permanent exhibition building because they had initiated this successful exhibition together with Prof. F. Roeber (later the director of the academy of arts), Mayor Marx and H. Lueg and F Krupp, two entrepreneurs, who were the spokesmen of the mining industry.

At the same time the city could develop extensive areas in the centre and along the riverbank. The former barracks grounds stretched from Kasernenstraße (Kasernen street) to the western side of Königsallee. The former palace (since 1872 only a ruin) had been demolished and the riverbank had been widened which now provided enough space for buildings with new architectural features.

Auf dem Weg zur rheinischen Metropole

Not only by the number of its inhabitants and its special atmosphere but also by buildings typical of cities of this time Düsseldorf aimed at presenting itself as a metropolis. A remarkable number of specific big buildings give an impression of the structure of the city before the First World War. These are e.g. the administration building of the steel association (“Stahlhof” – 1904), the “AOK” building (1904/05), the “Luisenschule” (1905-1907), the government building (1907 – 1911), the Provincial Court of Appeal (1910), the “Mannesmann” building (1910/11), the department stores “Tietz” (1907 – 1909) and “Carsch” (1914 – 1916) as well as the buildings of the district court and the country court in Mühlenstraße (1912 – 1921).

The “Dumont-Lindemann” theatre with performances throughout the year, the opera, the concert hall (built at the end of the 19th century and expanded in 1901), the “Apollo” theatre, numerous art exhibitions in the “Kunstpalast” and various other attractions provided for an unusually abundant cultural life. Several modern secondary schools were opened; not only the “Kunstakademie” (academy of arts) but also the “Kunstgewer-beschule” (college of arts and crafts) headed by Peter Behrens had an outstanding reputation.

In 1908/09 a municipal reform was carried out as the permanent growth of the city required new relationships to the adjacent villages. These had experienced an increase in population because of the improved traffic conditions but did not have the financial means to satisfy the needs of their growing population. The incorporation of Wersten, Stockum, Rath, Gerresheim, Ludenberg, Eller, Himmelgeist, Heerdt and Oberkassel doubled the size of Düsseldorf, the number of inhabitants rising by about 62,900.

Before the beginning of the First World War the population exceeded 450.000. Therefore it was not surprising that the award-winning design for “Düsseldorf as a city of more than one million inhabitants“ by Prof. B. Schmitz was highly appreciated when presented at the “Städtebau-Ausstellung für Rheinland, Westfalen und benachbarte Gebiete” in 1912. But the economic consequences of the First World War, the period of inflation and the French occupation foiled a lot of plans. Construction work came to an almost complete standstill followed by housing shortage and a state-controlled housing market.

Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg

Already in 1919 young artists such as Max Ernst, Jankel Adler, Arthur Kaufmann, Otto Dix, Otto Pankok, Adolf Uzarski and others met in Johanna Ey’s art gallery and founded the group of artists ”Junges Rheinland“.

Soon the first important examples of the architecture of the 1920s were erected. Nowadays they are considered as ground-breaking for the architecture of the Weimar Republic, although their construction was begun during a time when the economic situation was still bad : the “Wilhelm-Marx-Haus” (1922 – 1924), the “Industriehaus” am Wehrhahn (1924), the “Darmstädter und Nationalbank” (1924) in Königsallee, the “Pressehaus” at Martin-Luther-Platz (1924/25), the “Stumm-Verwaltung” (1923 – 1925) and the administration building of the “Phoenix AG” (1922 – 1926). An office-building company – in the foundation of which the city of Düsseldorf had played a major role – erected the two buildings mentioned at first. Different cooperatives and this office-building company were also in charge of constructing the first housing estates in Golzheim (from 1921 to 1923 and from 1922 to 1926).

Probably inspired by the exhibition centre founded by the mayor of Cologne, Dr. Konrad Adenauer, the mayor of Düsseldorf, Dr. Robert Lehr (1924 – 1933), realised that only a special event could do justice to the inhabitants’ undiminished zest and bring new glory to Düsseldorf as an exhibition place. The director of the children’s hospital, Prof. Arthur Schloßmann, had already energetically fought for founding the academy of medicine (1919) in Düsseldorf. He achieved that the ”Gesellschaft der Naturforscher und Ärzte“ held its conference in Düsseldorf in 1926. Therefore he is also considered the initiator of the “Große Ausstellung für Gesundheitspflege, soziale Fürsorge und Leibesübungen“ (Gesolei). This exhibition was not focused on industry and commerce but on human needs. Four hundred congresses and conferences emphasized its informative character. The permanent buildings by Prof. W. Kreis – the museums, the planetarium and the “Rheinterrasse” – closed the riverfront between the “Kniebrücke” and the government buildings. More than 7.5 million visitors – among them about three million from abroad – saw this exhibition.

View to the exhibition grounds of the “Gesolei“ with “Rheinterrasse”, “Ehrenhof” and planetarium – now the modern concert hall. Stadtarchiv (city archives) Düsseldorf. Photo from 1926.

In the following years large housing estates at Kaiserswerther Straße (Kaiserswerther street), the “Salz-& Schmitz-Häuser” at the “Theodor-Heuss-Brücke” and the housing estates at Karolingerstraße were built. Although all of these buildings were architecturally obliged to the Gesolei-buildings they nonetheless showed more characteristics of the architecture of the war and the early post-war years. During the second municipal reform in 1929 Kaiserswerth, Lohausen, Benrath, Itter and Urdenbach were incorporated into Düsseldorf.

The beginning of National Socialism and the Second World War were a serious setback for the city and put a stop to its cultural life. Shortly after the ”Machtergreifung“ the teaching staff of the academy of arts was exchanged : Paul Klee, Heinrich Campendonk, Ewald Matare and others had to leave, also Jascha Horenstein, the conductor of the city orchestra, and K. Koetschau, the director of the art museum. Galleries of modern art were closed and numerous artists were arrested, persecuted or banned from working. Innumerable works of art were removed, especially those by Jewish artists.

In 1937 the big exhibition ”Schaffendes Volk“ was organized – an event to which the city owes the “Nordpark” and the “Golzheimer Siedlung”. Some of the bigger buildings which had already been planned or the construction of which had begun in the 1920s – the main station, the police HQ and the regional revenue office – were completed in the 1930s.

A fresh start after the Second World War

The Second World War had caused enormous damage. The city looked like a heap of rubble. It had lost all its bridges as well as half of all its houses, industrial and public buildings. Nearly all of the churches had been destroyed apart from their enclosing walls. Just about 7 % of all buildings had remained undamaged. The first and foremost task therefore was to provide the citizens with housing resistant to winter and not in danger to collapse.

Düsseldorf – at first Headquarters of the British military government – became the capital of the federal state North Rhine-Westphalia in 1946. Friedrich Tamms – city planner since 1948 – was council officer for urban and regional planning from 1954 to 1969. The destroyed churches and important buildings were reconstructed – whenever possible according to their original plans and a reorganization plan from 1949 for a car-friendly city was approved. During the first years of the ”era Tamms“ his former colleagues from the “Arbeitsstab Speer” participated in all major building projects and Düsseldorf had the reputation of being quite conservative as far as its architecture was concerned. Only gradually a change took place: with numerous outstanding buildings the city was able to keep up with the international style of architecture at the end of the 1950s.

“Drei-Scheiben-Haus”, also called “Thyssen-Haus”, was built in 1960 at the edge of the “Hofgarten” by two architects from Düsseldorf, Helmut Hentrich and Hubert Petschnigg. The building has 26 floors with a total height of 96 metres.

The “Drei-Scheiben-Haus”, the new theatre, the “Mannesmann” building, the new state gallery, the new parliament near the TV tower as well as the buildings by Frank O. Gehry in the harbour, the “Stadttor” and numerous other new administration and media buildings contribute to the constantly changing appearance of Düsseldorf. Old and new are at close quarters but harmoniously complement each other. A fact that Peter Behrens had aptly put on parting from Düsseldorf (1907): “Heinrich Heine is right: This city is so beautiful that nobody will be able to spoil it completely – no matter how hard they try.“

At the moment (2000) Düsseldorf has approximately 570,000 inhabitants. Together with Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Munich it is nationally and internationally one of the most important economic centres. The following facts emphasize its importance as a centre for international trade: Düsseldorf has the biggest settlement of Japanese in Germany, the third largest airport of the Federal Republic (more than 16 million passengers in 2000) and is the second largest banking and securities trading centre. But Düsseldorf is also a market of creativity, the arts, fashion and well-known for its international trade fairs. About 1000 companies of the information and communications industry with more than 26,000 employees have their offices in Düsseldorf; more than 200 galleries organise exhibitions and about 600 artists live and work here; more than 900 advertising agencies – some of them international companies– with approximately 6,500 employees are based here. Düsseldorf also has various colleges and universities, e.g. the “Heinrich-Heine-Universität”, the academy of arts and the “Robert-Schumann-Hochschule”.

Urban life on the banks of the river Rhine with the “Schloßturm” dating from the middle of the 16th century and “St. Lambertus Basilika” dating back to the 8th century.

The international atmosphere of the state capital Düsseldorf is also reflected in its cosmopolitan and friendly population, its numerous leisure facilities and the attractive landscape on both sides of the river. In other words: Düsseldorf is always more than worth a visit. Come and experience the city on a balmy summer evening – sitting on the Rhine-promenade and drinking a glass of “Altbier” (top-fermented dark beer) to end an eventful day in pleasant company.

Ralf A. H. Thonemann

Düsseldorfer Schloss

Highlights of the state capital (a selection)

Düsseldorfer Schloss

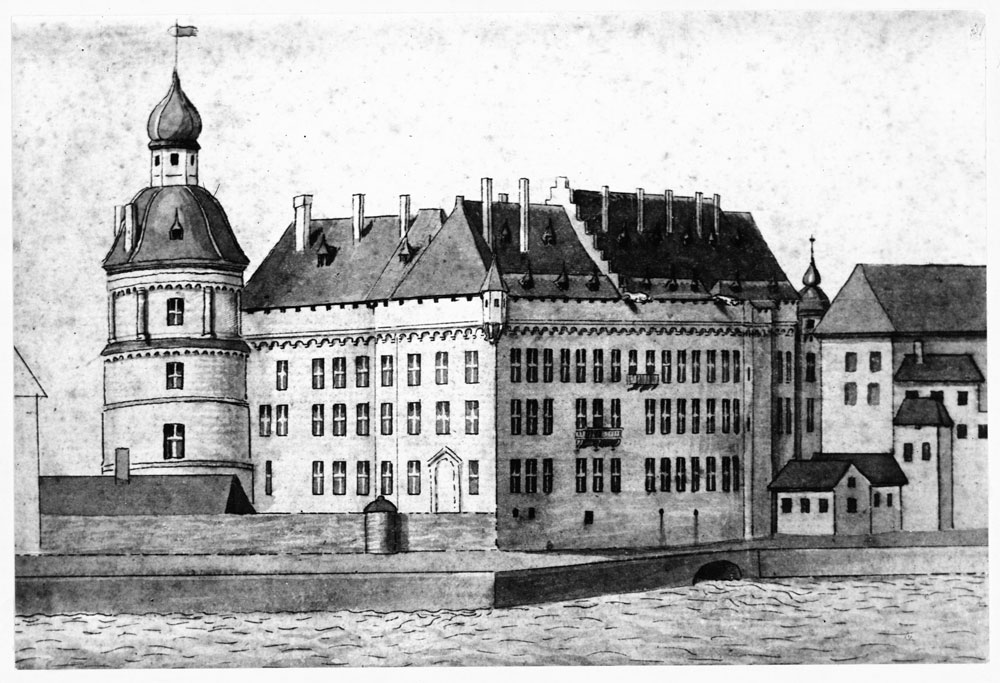

The castle of the earls of Berg (later the dukes of Jülich-Kleve-Berg) was probably built after Düsseldorf had been granted the status of a town (in 1288) and dominated the riverfront for centuries. In general its construction (at first probably only a fortified dwelling house) is estimated at around 1324 when there were plans to collect customs duty in Düsseldorf. The castle, mentioned in official documents from 1386 on, had already undergone considerable expansion at that time. Presumably in the last two decades of the 14th century and at the beginning of the 15th century a complex consisting of three wings was built. It opened up towards the town and had towers at the end of the northern and southern wing. A wall stretched between these towers and a water-filled moat surrounded the whole complex. The northern Düssel which flowed under the castle did not only feed the above mentioned moats but also formed a small moat for waste disposal in front of the long wing facing the Rhine. The palace itself was situated right next to the shipyard.

After the fires around 1490 and 1510 the castle was dilapidated. Between 1522 and 1529 it was renovated – first by Duke Johann III of Jülich-Kleve-Berg and then by his successor Wilhelm der Reiche. Alessandro Pasqualini, the master builder from Bologna, was in charge of the conversion. Around 1551 he finished the round tower (which still exists today) and added a fourth polygonal store that was structured by Tuscan semi-columns and originally had a hemispherical dome crowned with an onion-shaped lantern.

The palace was one of the favourite residences of the last dukes of Jülich-Kleve-Berg. In 1585 it served as setting for one of the most glittering celebrations in the town history: the marriage of Duke Johann Wilhelm to the Countess Jakobe von Baden.

Equestrian picture of the Elector Johann Wilhelm, painted by Jan Frans Douven in 1703. Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, Inv.Nr. 91.

Of the sovereigns of Pfalz-Neuburg the Elector Johann Wilhelm spent all his life in Düsseldorf and had the palace modernised and sumptuously furnished. From 1709 to 1714 he even had a separate gallery built for his collection of paintings. It was connected to the palace and one of the first of its kind in Germany.

”Close to the palace there is the building finished in 1710. It houses the famous gallery of Düsseldorf – one of the three most distinguished collections of paintings in Germany“ Ludewig Wilhelm Gilbert in 1792.

The court buildings also had a theatre, an opera and a “Ballspielhaus” (a building for playing ball games). Near the palace tower were the living quarters of the servants which had been remodelled together with some other outbuildings in 1699.

“Düsseldorfer Schloss” – view from the west. The picture shows the building with roof and floors in the early 18th century. Drawing from around 1800, based on a lost original. Stadtmuseum (city museum) Düsseldorf.

After Johann Wilhelm’s death his successors did not live in Düsseldorf any longer. They had the furnishings, the collections and the library gradually transferred to their new residence in Mannheim so that the palace slowly became uninhabitable.

Elector Karl Theodor commissioned his master builder J. H. Nosthoffen to renovate the buildings and he added floors to the entire complex. During a bombardment by French troops in 1794 the palace was destroyed by fire and remained a ruin until the beginning of the 19th century when it housed the newly-founded academy of arts.

Professor Rudolf Wiegmann of the academy of arts planned the reconstruction of the completely demolished northern wing which was assigned to accommodate the provincial parliament; on the day when the foundation-stone was laid, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV came to Düsseldorf.

For the tower – at that time still a ruin – Wiegmann designed an open upper storey of octagonal shape, structured by double arcades and decorated with a balustrade. But in 1872 the palace (by then already called the academy of arts) was once again destroyed by fire.

The ruin of the palace after the devastating fire in March 1872. On the left side of the picture: the palace gate by Pasqualini next to the ruin of the former academy of arts. On the right side: the northern wing (next to the palace tower). It had accommodated the “Ständehaus”. After the fire the “Ständehaus” moved into a building at the “Kaiserteich”. H. and E. Becker, 1872. Stadtmuseum (city museum) Düsseldorf

In 1882 the ruin was sold to the city of Düsseldorf. The council decided to pull it down and in 1892 granted the necessary funds for extending the palace tower which was still in relatively good condition. When the “Oberkasseler Brücke” (Oberkassel bridge) was opened to traffic in 1898 plans were made for laying-out the now empty space at the riverfront. In 1909 the dilapidated balustrade of the tower was removed and replaced by a flat tent roof. During an air raid in the Second World War (1943) the tower burnt out. In 1950 it was only pro-visionally repaired and from 1978 to 1983 basically restored. Today it accommodates the valuable collection of inland shipping of the “Stadtmuseum” (city museum)– the so-called “Schiffahrts-Museum” (shipping museum).

From 1999 to 2001 the tower was again renovated and fitted out with a cafe in the so-called lantern (the upper storey) from where you have a wonderful view to the old town and the river Rhine.

The remains of the palace: the palace tower on the riverbank. Today (2002) it accommodates the “Schiffahrts-Museum” (shipping museum) with a cafe in the lantern (the upper storey).

Heinrich Heine

Heinrich Heine

His life and his works

Heinrich (christened Harry) Heine was born in Düsseldorf on 13.12.1797. From 1807 to 1814 he attended grammar school. One year later Heine left his home town and completed a training as a bank clerk in Frankfurt and Hamburg. He studied law in Bonn, Göttingen and Berlin but also attended lectures on history and philology.

During a hiking tour in the “Harz” Heine visited Goethe in Weimar on 2.10.1824. In June 1825 he converted from Judaism to Christianity; one month later he did his doctorate in law. From his time as a student date ”Gedichte“ (1822) and two tragic-dramatic essays (tragedies with a lyrical intermezzo), but only ”Reisebilder“ (two volumes, 1826 to 1827 including ”Harzreise“, ”Nordsee“, the book ”Le Grande“; two further volumes 1830/31 including ”Reise von München nach Genua“ and ”Bäder von Lucca“) were a big success – alternating witty descriptive prose and lyric poetry interludes written in a nimble and elegantly chatting style. From that time on Heine was able to live as an independent writer.

In the back-building of this house in the old town, Bolkerstraße 53 (Bolker street), Heinrich Heine was born on 13.12.1797.

Heine collected the verses that were scattered in ”Reisebilder“ and published them together with a lot of new ones in ”Buch der Lieder“ (1827) which became the most successful German collection of poems and established Heinrich Heine’s world-wide reputation as a lyric poet.

In 1831 Heine went to Paris as a correspondent for the ”Allgemeine Zeitung“ (Augsburg) and only revisited Germany briefly in 1843 and 1844.

On 31.8.1841 he married Eugenie (Mathilde) Mirat (* 1815, † 1883).

For quite some time Heine received an honorary pension from the French government because of his merits (acquaintance with Balzac, V. Hugo, Dumas the Elder, Lamartine, George Sand, A. de Musset, G. de Nerval and others). As a writer he tried to mediate between Germany and France by means of introducing French art and liberality to Germany and German literature and philosophy to France. To this end ”Geschichte der neueren schönen Literatur in Deutschland“ (two volumes; extended by the German Romantic period it was published as ”Die Romantische Schule“ in 1836) and ”Französische Zustände“ were published in 1833. In 1834 the first volume of „Salon“ (with ”Französische Maler“, poems and the fragment ”Aus den Memoiren des Herrn von Schnabelewopski“) and ”Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland“ (in the second volume of „Salon“ together with ”Frühlingslieder“) followed.

The German parliament banned the works of Heinrich Heine and those of the writers known as the ”Jungdeutsche“ in 1835.

In 1837 the third volume of „Salon“ was published (including “Florentinische Nächte“ and ”Elementargeister“). In the same year Heine attacked Platen in ”Bäder von Lucca“ and W. Menzel in ”Über den Denunzianten“, in 1840 he settled the score with L. Börne. In 1840 Heine published the fourth volume of „Salon“ including „Rabbi von Bacharach“ and ”Über die französische Bühne“, poems and romances. A journey from Paris to Hamburg inspired his epic poem ”Deutschland, ein Wintermärchen“ (1844) in which he mercilessly exposed German weaknesses by means of biting wit. In his epic poem ”Atta Troll“ (1847; partly in magazines in 1843) he ridiculed literature written for political purposes only and advocated the independence of genuine poetry instead. Heine wrote the poem ”Die Göttin Diana“ in 1846, ”Doktor Faust“ in 1847 and ”Geständnisse“ and ”Memoiren“ between 1853 and 1856.

In ”Neue Lieder“ (1844) the lyric tones of voice took second place to political tendencies; at the same time Heinrich Heine – following Saint-Simon – preached the cult of sensual pleasures intoxicated by beauty. His most genuinely personal tones of voice are to be found in ”Romanzero“ (1851) and its sequel (in the third volume of ”Vermischte Schriften“ – 1853/54) which were written when he was already suffering from an incurable disease which affected his spinal cord. Constantly in pain Heine had been confined to bed since 1848. At the end, when he was helpless and became more and more isolated, his last lover ”Mouche“ (Elise Krinitz, * 1830, † 1897) cared for him. Heine died in Paris on 17.2.1856.

Heinrich Heine – Painting by M. Oppenheim, 1831. “Kunsthalle Hamburg”.

His personality and his influence

Heinrich Heine was one of the most important and gifted talents in the post-Goethe 19th century. In the tradition of Eichendorff’s and Wilhelm Müller’s four-line-poems Heine combined the magic and the variety of sentiments of late-Romantic poetry with the reflectiveness and the scepticism of the intellectual who was – similar to Byron – full of inner conflict.

Too conscious and too confused to be able to abandon himself to the pathos of a sentiment, and too honest to feign an innocence of feeling he did not have any more, Heinrich Heine introduced a Romantic irony to lyric poetry which included a witty reflexion on his own point of view. This led to the frequent – partly shrill-cynical, partly gloomy-dissonant – changes of mood in his poems.

At first sight Heine’s songs and ballads seem to be rather simple in style. However, a closer look reveals their artistic perfection. Some of them have become quite popular, especially in their musical arrangement by Schubert and Schumann. The satirist Heine was of scathing shrewdness. With his ingenious, emotional and ironical prose he created a literary style which nowadays is often used in the sections of a news-paper dealing with culture, literature and entertainment.

Equally impressed by Hegel and Saint-Simon Heine sympathized with the “Linkshegelianismus” in his aggressive and partly revolutionary attitude towards state and church (acquaintance with Karl Marx in Paris).

Heine’s ambivalent and contradictory personality can be explained by the transitory era he lived in – an era in which the ethical and metaphysical obligations of the Idealistic epoch were fading. His literary works are nonetheless homogeneous and complete, his wit a means of synthetizing intellect and emotions, the individual and the universal.

Heinrich Heine’s literary influence in Europe was extraordinary. His poems were translated into many languages and the notion of German Romanticism abroad has been considerably shaped by Heine. But from the beginning Heine and his literary works also met with hostility – the culminating point of the dispute about Heinrich Heine was around 1900 (K. Kraus, “Heine und die Folgen“, 1910).

Heinrich-Heine-Institute

Anyone who is looking for the spirit of Heinrich Heine in Düsseldorf should pay a visit to the “Heinrich-Heine-Institut” in Bilker Straße 12-14 (Bilker street) as it is museum, memorial and research institute at the same time. A permanent exhibition gives an introduction to the life and works of the poet. The institute stores original manuscripts (about half of all Heine autographs in the whole world) and further authentic documents. Re-searchers on Heine from all over the world keep coming to the institute as guests.

Heine-Monument

On the occasion of the 125th anniversary of Heine’s death an eventful history of a monument came to its end: Bert Gerresheim’s Heine monument – donated by Dr. Stefan Kaminsky – was set up at Schwanenmarkt in 1981. A first initiative for a Heine monument in Düsseldorf came from the Empress Elisabeth (Sissi) of Austria in 1888 but failed because the Prussians were ruling over Düsseldorf at that time. Later the citizens‘ donations for the monument were used to purchase Heine’s literary estate.

In 1932 the artist Georg Kolbe won the first prize in a competition for a Heine monument. His bronze sculpture of an aspiring young man could not be set up at the “Ehrenhof” until after the Second World War.

The “Kunstverein” donated the torso of a girl ”Harmonie“ in the “Hofgarten” in Heine’s honour in 1953. Different from all these allegorical sculptures Gerresheim’s ”Fragemal“ critically reflects the possibilities of a monument at the present time. His monument is a distorted sculpture which breaks up Heine’s death-mask and surrounds it by numerous symbols.

The Heine monument at Schwanenmarkt – a sculpture of his physiognomy – created by Bert Gerresheim from Düsseldorf in 1981.

The Hofgarten

The “Hofgarten” – ”one of the most beautiful and appealing parks of modern times“ (”Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz“) covers 27 hectares – stretching from “Schloß Jägerhof” to the river Rhine.

This peaceful park owes its existence – although this may sound paradoxical – to hostilities. The Seven Years‘ War had seriously damaged the land in Pempelfort which was situated outside the defences. Count Franz Ludwig Anton von Goltstein, the elector’s governor, did not only want to have these devastations removed but also tried to boost a kind of job creation scheme for poor and unemployed inhabitants.

View of a part of the pond “Landskrone“ in the “Hofgarten”.

In 1769 the oldest part of the park was laid out in classical French style according to the plans of Nicolas de Pigage (who also designed the park of “Schloß Benrath”). About 700 inhabitants were employed for levelling and planting. The “Hofgarten” – at that time expanding from “Schloß Jägerhof” to present-day Pempelforter Straße (Pempelforter street)– was decorated according to the dominating courtly taste with statues, plaster lions and even a Chinese pavilion at the basin of the ”Jröne Jong“. All these splendours fell victim to military plannings.

Between 1797 and 1799 the French – who had taken Düsseldorf during the turmoils of the revolutionary wars – turned the town into a fortress and destroyed many trees including the pavilion. After the “Frieden von Lunäville” in 1801 the French had to withdraw and the fortifications were razed to the ground. That left scope for a further expansion of the park which was begun in 1804 according to designs of Maximilian Weyhe. In 1811 Napoleon specifically approved of this project by issuing a decree with which he handed over the grounds of the former ramparts to the inhabitants of Düsseldorf for turning them into green areas. Weyhe created a landscape garden in English style. His skill becomes immediately apparent in his arrangement of rising grounds and gentle valleys – thus miraculously creating the impression of a „natural“ landscape. One example of his brilliant achievements is the combination of the hills “Landskrone”, “Hexenberg”, “Ananasberg” and “Napoleonsberg” with the adjacent extensive meadows.

Weyhe also redesigned big parts of the old French gardens, preserving only the “Reitallee” and the “Seufzerallee” next to the Düssel (river Düssel).

The “Hofgarten” was an integral part of the town planning at that time. Despite their different personalities and opinions Weyhe, the landscape gardener, and Adolph von Vagedes, the town planner, worked in close and fruitful co-operation. The area of the former fortifications was supposed to be converted into a continuous ring of parks and promenades. The parks at “Spee’scher Graben, Schwanenspiegel”, “Königsallee”, “Hofgarten” and “Heinrich-Heine-Allee” were finished by the middle of the 19th century – M. Weyhe having been in charge of their lay-out. “Ananasberg” and “Napoleonsberg” simultaneously mark the end of Königsallee and Heinrich-Heine-Allee, respectively; the focal point of the park is the “Goldene Brücke” across the pond “Landskrone” from where you can see as far as “Schloß Jägerhof” in one direction and as far as the old town in the other.

On the whole the park has been preserved in this condition until today. Only some of its smaller parts and the garden behind “Schloß Jägerhof” have been covered with buildings. The “Ehrenhof”, built in 1926 for the exhibition “Gesundheitspflege, soziale Fürsorge und Leibesübungen“ (Gesolei) and separating the park from the riverfront, presents a quite appealing sight due to the homogeneity of the buildings.

The variety of landscapes in the “Hofgarten” also offers a setting for numerous monuments. A statue of Maximilian Weyhe (1850 by C. Hofmann) is near “Schloß Jägerhof”. Close to Louise-Dumont-Straße there is a statue of the actress, modelled after a portrait bust by Ernesto de Fiori (1930).

At the southern edge of the park a bronze statue (1901 by C. Buscher) commemorates the poet Karl Immermann (*1796, † 1840). The “Goldene Brücke” (built by Anton Schnitzler from 1852 to 1853) across the pond “Landskrone” leads to the “Märchenbrunnen” (1905 by M. Blondat).

South of the bridge is the impressive war-memorial by K. Hilgers (1892). In the direction of the river Rhine the monument of the poet Heinrich Heine (*1797, † 1856) is situated on “Napoleonsberg”. Modern sculptures like Vadim Sidur’s “Mahner“ and Henry Moore’s ”Liegende Figur in zwei Teilen“ are valuable additions to the artistically created landscape of the park.

Statue of Maximilian Weyhe, the landscape gardener (*1775, † 1846), who created the “Hofgarten” (1850 by C. Hofmann).

Märchenbrunnen

This group of children by the French sculptor Max Blondat was one of the most admired works of art at the “Gartenbau- und Kunstausstellung” in 1904. The society for improving the appearance of the city entered into negotiations with the artist and in the following year a contract was made including details of the design and an agreement concerning the sculptor’s assistance in case of possible future damage. Already at that time the small grass-plot at “Ananasberg” was assigned as the place for erecting the sculpture.

At the turn of the century Max Blondat was an unusually successful artist. By exhibitions in Europe and America his works of art became well-known. The “Märchenbrunnen” is not only to be found in Düsseldorf but also in Odessa (Russia), Zurich (Switzerland), Dijon (France) and Denver (USA). The sculpture, chiselled from Blanc-Clair marble, was finished in 1905.

Three children – snuggling up to one another – are sitting on a stalactite pedestal from which seem to hang wet moss and moist lichen. The children are looking at three bronze frogs on the opposite edge of the basin where thin water jets are spurting out of the frogs‘ mouths.

The “Märchenbrunnen” chiselled from Blanc-Clair marble by Max Blondat (completed in 1905) – a replica set up at the edge of “Ananasberg”, near the “Goldene Brücke”. The original can be admired in the Stadtmuseum (city museum).

The beautiful railing does not belong to the original design. Soon after the sculpture had been put up it was necessary to surround the fountain „with a railing not too low and tastefully forged, its tips to be provided with barbs in order to prevent people from climbing over“. At times a policeman had to protect the sculpture from wilful damage. As there was no end to that kind of vandalism repairs by the sculptors Julius Haigis and Fritz Coubillier were necessary. Unfortunately, wilful damage led to the replacement of the original by a replica from shell-lime (donated by Walter Kessler) in 1985. The original sculpture was restored and got a place in the Stadtmuseum, Berger Allee in 1998.

The pleasing forms of the fountain later gave rise to the question whether the sculpture represented more than a mere genre-motif. Even though the three frogs and the three naked young girls contradict the fairy tale ”Froschkönig“ the vague correspondence to this fairy tale might have fascinated people and after some years the name ”Märchenbrunnen“ was generally accepted.

The fountain seems to be a symbol of a happier time and its attitude of life. Over and over again requests were made asking permission for copying this work of art. The sculpture perfectly adapts to its natural surroundings and the still lasting charm of the figures together with the interaction of the delicately chiselled marble figures and the decoratively forged railing make it one of the most appealing monuments in the city.

The Nordpark

After only one and a half years this park was laid out for the ”Große Reichsausstellung Schaffendes Volk“ (1937) according to the designs of the director of the gardening authority – Willi Trapp.

If you enter the park from Kaiserswerther Straße (Kaiserswerther Street) your attention is drawn to the artificial fountains forming big archs along the whole length of the 170-metre-basin and the big fountain at the opposite end.

Formerly only some brickworks were located in the mainly undeveloped fallow grounds between Reeser Platz and Lantz‘scher Park where the soil was of only moderate quality. The park – designed as an expansive area with axial ground plan – could be laid out according to purely architectural principles as no natural restrictions had to be considered.

The paths leading to the different parts of the park are designed as clear main and side axes and therefore have a strong visual effect on the visitor. A good example for the eye-catching axes typical of the park is the “Kanalgarten” with the “Fontänenplatz” and the continuation to the Rhine which look like a corridor deco-rated with flowerbeds.

The magnificent stock of trees has its origin in several hundred big trees which were taken from other parks and cemeteries. Numerous conifers came from private parks in the surroundings of Düsseldorf. The exhibition site for ”Schaffendes Volk“ had a total area of 78 hectares, 28 hectares of which accounted for the park. At the present time the park covers a total area of 36.6 hectares: 22 hectares of lawn, 7 hectares of bushes and 7 hectares of paths.

On the whole, the park nowadays looks like it did in 1937. Only the big flower hall – like all the other exhibition buildings designed by the architect Professor Fritz Becker from Düsseldorf – does not exist any more. Just a big round flowerbed – in the middle of which the slim cinematographical sculpture by George Rickey gently moves in the breeze – is reminiscent of this building. Some of the sculptures in the Nordpark have been preserved from their date of creation, e.g. the huge ”Rossebändiger“ (designed by Edwin Scharff) at the entrance, ”Sitzende“ (Johannes Knubel) as well as the four sculptures – bigger than life-size – along the big water-basin : all that remained of the original 12 sculptures are ”Bauer und Bäuerin“ (Kurt Zimmermann), ”Winzerin“ (Alfred Zschorsch), “Falkner“ (Willi Hoselmann) and ”Schäferin“ (Robert Ittermann) which is now in Benrath.

In 1975 the Japanese community of the state capital gave a Japanese garden to the city of Düsseldorf as a gift. This garden – located in a part of the park – is a most valuable asset. It cost 1,000,000 EUR and covers an area of 5,000 square metres. This oasis of peace and quiet was planned by the Japanese landscape gardener Iwakii Ishiguro and his son. The project was carried out by the master gardener Sakumo and six assistants. From time to time Japanese gardeners come to Düsseldorf for its cultivation and maintenance. The garden combines all the picturesque features of a typical Japanese garden: a cascade, ponds and islands, stones and plants (especially pines, azaleas and Japanese cherry trees) as well as the special modelling of the ground. This part of the Nordpark is very appealing at the time when the azaleas are in full bloom. A special pumping equipment supplies the running water typical of a Japanese garden.

The “Löbbecke-Museum” and the “Aquazoo” have been the architectural highlight of the park since 1987. The architects Dansard, Kalenborn & Partner designed the new buildings because their project had won the competition solely held for this purpose in 1975. With this complex the park has an architectural centre; by different levels varying in height the visitor is led to the central area: the tropical hall with its glass roof. The new building joins the scientific collection and the aquarium with the terrarium to a functional whole.

St. Rochus’ Church

The history of this church leads back to the 15th century. There is evidence that Saint Rochus had been worshipped in Pempelfort since 1448. Wayside shrines, small houses for prayer and finally a small chapel were the stages of worshipping Saint Rochus in Pempelfort – a phenomenon which had first begun during the plague of 1448 but kept flaring up in difficult times. Also during epidemics like cholera or epidemic diseases of animals the people turned to Saint Rochus for help.

A modest chapel built in 1667 became the destination for pilgrimages and was used for mass. The village of Pempelfort (belonging to Düsseldorf since Düsseldorf had been granted the status of a town in 1288) was situated outside the town gates up to the middle of the 19th century. When Düsseldorf became the commercial centre on the Rhine due to the industrialization shortly before the turn of the century the district Pempelfort also expanded.

At the end of the 19th century the chapel had become too small, the parish of St. Rochus was founded. On 2.5.1894 – the time of construction having taken three years – the parish moved to a Romanesque church built by the architect Josef Kleesattel from Düsseldorf, who had taken the church St. Aposteln in Cologne as a model. In the Second World War (1943) St. Rochus‘ church was destroyed apart from the church-tower.

The Romanesque church built by the architect Josef Kleesattel from Düsseldorf in 1894. The time of construction took three years. Model was the church St. Aposteln in Cologne. Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf. Photo from 1908.

In 1953 a decision in favour of a new church was made. The tower, which had been preserved (similar to the “Gedächtniskirche” in Berlin), and the new building designed by the architect Paul Schneider-Esleben were supposed to form a functional whole. The modern church is a detached building and consists of three parts. Its structural steel work is crowned by a copper-plated dome consisting of three parabolic-shaped shells. The egg-shaped dome, which is supported by 12 columns, represents life. This modern church is a building in the tradition of ancient symbolism: the three parts of the ground-plan stand for the Holy Trinity and the 12 columns for the 12 apostles as the spiritual foundation of the church.

The interior furnishings are by Ewald Matare, Professor of Sculpture at the academy of arts in Düsseldorf and by the architect Paul Schneider-Esleben. The large figure of the triumphant, crowned Jesus (Matare himself called it ”Auferstandener“) which dominates the room was created during the war in 1940. The slim upwards-striving shape of the white-varnished wooden figure connects the assembly room to the dome. From 1940 date Matare‘s 14 “Kreuzwegstationen” (depicting the Passion).

Paul Schneider-Esleben designed the dove in the centre – the symbol of the Holy Ghost – as well as the seats of the priests and acolytes, the altar, the tabernacle and the pulpit.

The sculptor Bert Gerresheim created a monumental bronze sculpture of the crucified Jesus for the “Katholikentag” held in Düsseldorf in 1982. After the end of the convention the sculpture was put up on the facade of the church-tower. Gerresheim dedicated it to the Franciscan father Maximilian Kolbe who was murdered in Auschwitz.

In the foreground: the preserved church-tower with the bronze sculpture of the crucified Jesus by the artist Bert Gerresheim from Düsseldorf. In the background the church building by the architect Paul Schneider-Esleben dating from 1953: a central building consisting of three parts, crowned with a copper-plated dome in the shape of an egg.

After the church (since 1988 classified as a historical building) had undergone extensive renovation it was consecrated by Cardinal Joachim Meissner from Cologne in September 1991.

St. Rochus‘ church is one of the biggest churches in the state capital and as a listed building widely-known outside Düsseldorf.

Schloss Benrath (Palace of Benrath)

In the former village of Benrath in the south of the city (since 1929 belonging to Düsseldorf) the Elector Karl Theodor von der Pfalz-Sulzbach had a palace built by Nicolas de Pigage from Mannheim from 1756 to 1773. This baroque building is set in the middle of an extensive park which stretches to the banks of the river Rhine. The original building – built by Johannes Lolio, called Sadeler – which had a zoological garden and was surrounded by water, had been pulled down in 1755.

The „garden palace, plain and elegant as it was the fashion at the time in Paris“ (Dehio) is situated in the axis of the palace pond with two lateral wings and gate buildings. The paths of the park lead to the domed hall in the centre; behind the whole complex is the pond ”Spiegelweiher“. The main building shows the typical features of a “maison de plaisance” – a style developed during the French rococo. The curved roof with its oval windows perfectly fits into the whole outline. The sandstone sculptures at the terrace and in the park were created by the sculptor Anton von Verschaffelt.

The front windows give the wrong impression that there is only one floor between the base and the attic roof, although, in fact, it is a four-storeyed building. This way Pigage had space for 80 rooms despite the relatively small floor area.

Aerial view of the baroque palace with its two wings and the park which borders on the river Rhine. The Elector Karl Theodor von Pfalz-Sulzbach had this well-preserved garden palace built by Nicolas de Pigage from Mannheim between 1756 and 1773.

The halls facing the park, the vestibule and the domed hall in the centre are decorated with lavish marble stuccowork, ceiling paintings, mirror-frames with gold-leaf ornamentation and parquet floors with marquetery in Louis XVI-style. Important artists – among them the director of the academy of arts Lambert W. Krahe (ceiling paintings) – contributed to the interior design of the rooms.

Passing through the vestibule the visitor enters the magnificent domed hall which takes up the whole height of the building and was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome and the Roman baroque. The marble floor displays a star in its middle. Towards the top the hall gets brighter and finally ends with the “Götterhimmel” (Diana with her entourage by Krahe); a music-gallery is hidden in the dome. Attached to this hall are the two garden halls and – in the middle of the narrow sides – the bedrooms, dressing rooms and bathrooms of the elector and his spouse. The beautifully curved main stairs lead to the upper storey with the chapel. All rooms are fitted out with valuable furniture, clocks, paintings, chandeliers and “Frankenthal” china.

The architectural task, masterly carried out by Pigage, reflects the change of the sovereign’s perception concerning his own role. His official functions receded into the background while more importance was attached to his private needs as far as his living quarters were concerned. Chambers of comfortable luxury, bedrooms with bathrooms as well as the rooms for the servants are grouped around two partly hidden inner courtyards. The private living quarters of the elector and his wife are symmetrically arranged. Each of them had his or her own private rooms – the lady in the east and the gentleman in the west.

“Schloß Benrath” stretches to the river Rhine. It was designed according to Pigage’s instructions and corresponded to Lenotre’s ideas. The basic idea is its strictly geometrical shape which is even reflected by the axial character of the paths in the woody parts of the park. The eastern wing of the palace with the French garden and the western wing with the English garden clearly emphasize the harmonious combination of palace, park and ponds. Different ground levels create an optical effect of spatial expanse. In 1841 the English garden at the western wing of the palace was remodelled by Maximilian Weyhe.

Schloss Jägerhof (Palace of Jägerhof)

This hunting-lodge dates back to the late baroque. It is situated at the head of the “Hofgarten” and the beginning of the “Reitallee” in the district Pempelfort.

Johann Joseph Couven, the master builder from Aachen, and Nicolas de Pigage, the sovereign’s architect, built this hunting-lodge from 1752 to 1763 as a residence for the masters of the huntsmen.

Two wings protruded from the main building. The courtyard was separated from the “Hofgarten” by a wrought-iron fence, which was removed in 1809 when the park was redesigned by Weyhe.

“Schloss Jägerhof” (photo by Robert Franck, 1900).

The photo shows the hunting-lodge built in the second half of the 18th century according to Johann Joseph Couven’s plans. In 1826 Prince Friedrich commissioned Adolf von Vagedes with the construction of two lateral wings, which were pulled down in 1909..

Until 1795 – when it was looted by republican troops “Schloß Jägerhof” was the residence of the masters of the huntsmen. From 1806 to 1808 it served as residence for Joachim Murat, the grand duke of Berg, who had been appointed by Napoleon.

In 1811 Napoleon himself stayed in “Schloß Jägerhof” while visiting Düsseldorf.

In 1820 Adolf von Vagedes added more storeys to the extensions and also renovated the interior when Prince Friedrich von Preussen chose to live there. “Schloß Jägerhof” was the residence of the dynasty Hohenzollern until 1885 when it became the seat of the emperor’s adviser.

In 1909 the city of Düsseldorf purchased “Schloß Jägerhof” and its gardens which were divided into lots and sold. Because the wing buildings jutted out beyond the alignment of houses in Jacobistraße by 1.70 metres, they were pulled down in 1910.

During the French occupation after the First World War “Schloß Jägerhof” was the seat of the commander’s office.

During an air raid in the Second World War (Pentecost 1943) most of the palace was destroyed. The architects Helmut Hentrich & Hubert Petschnigg rebuilt the external walls in their original baroque style and mostly respected the former baroque structures indoors. The construction was completed in 1954.

At the moment (2001) “Schloß Jägerhof” houses the “Goethemuseum” and the “Schneider” collection of china.

View from the “Reitallee” to “Schloß Jägerhof”. The hunting lodge was rebuilt by the architects Helmut Hentrich & Hubert Petschnigg in 1954.