The Thonemann Branch in Australia

On 6 May 1787 Johann Heinrich Thonemann (* 15.05.1758 in Scherfede, † 25.03.1814 in Scherfede) married Eva Margareta Engemann (* 05.01.1765 in Rimbeck, † 25.03.1814 in Scherfede) in Scherfede. This marriage produced twelve children, among others Augustus Louis Emilius Thonemann (* 14.12.1803 in Scherfede, † 29.06.1852 in Höxter). Augustus Louis Emilius was married twice. Together with his second wife (oo 1829 in Münster) Caroline Fredericke Jacobi he had three children, Louis (* 06.09.1830 in Berlin, † 11.11.1882 in Carlton/Australia), Emil Julius (* 03.02.1832 in Berlin, † 14.10.1874 in Bad Driburg) and Malvine († 1893 in Höxter). Emil Julius Thonemann, the founder of the Australian family brach, was married to Mary Noble and their son Frederick Emil (* 1860 in Melbourne/Australia, † 1939 in Melbourne) – one of eleven children – was a stockbroker in Australia.

Frederick Emil Thonemann, my father, was the son of Julius Emil, who sailed to Australia in 1854, on the “Antoinette Cezard”. Both Emil, and his brother Louis were appointed consuls successively to Victoria, Australia, from the Austro-Hungarian Emire (1871 – 1875). The exact reason for their emigration and subsequent gaining of British Status under Queen Victoria, are not known at present. The most likely cause is political unrest in Germany.

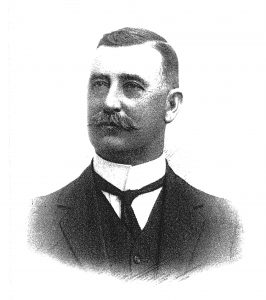

My father was born in 1860 in Melbourne, and was educated at the Melbourne Church of England Grammar School, in St Kilda Road. He had a brother named Louis Arnold, and a sister (or stepsister) named Minna Augusta. Neither of the latter mentioned married.

Frederick Emil Thonemann (*1860, †1939)

My father started work as an ‘Office boy’ – possibly this was in his father’s early business. His unique ability to judge the quality of wool by the feel in his fingertips made it possible for him to set up a wool broking business in the firm Thonemann and Lange.

My father’s business prospered and he was able to set up as a stockbroker. F Thonemann and Sons – National Mutual Building, Melbourne. He retired in 1930 and the business was continued by his eldest surviving son Eric.

My father’s business interests were many and varied, including a large cattle station in the Northern Territory called Elsey and Hodgson, of 4 million acres, on the Roper River. When my father died in 1939, the cattle station was sold. The land is immortalised in a book, and a film ‘We of the Never-Never’. A book by my stepbrother Eric (who managed the Elsey for some Years) has recently been discovered in the British Library. It is titled ‘Tell the White Man’, and is written in the first person, as the story of the life of an Aboriginal woman, whose tribe resided in this part of Australia. (Published in 1949, in Australia, by Collins Publishers).

About 60 miles north of Melbourne, in land part-cultivated and part rain forest, my father bought some 1000 acres, which was named ‘Bennak’. I remember this property, high above the surrounding country, he built a great house with fischponds, flower gardens, croquet lawn and vegetable garden. The property was surround by a 20-foot high holly hedge. To reach Beenak, a train from Melbourne stopped at Yarra Junction. There one transferred to a narrow gauge railway, which chugged up the valley to Williamstown. This train used to bring down the cut timber from the rain forest. In his Chevrolet van over muddy roads my father managed to drive us the three miles to the property.

In 1919 the house itself was destroyed by fire. Thereafter, when anyone from the family visited, they lodged with the farmer in a house lower down the land. (The actual land was not sold until 1960’s, having been bequeathed to his widow)

Beenak was some 1700 feet above sea level, surrounded by a state forest of enormous eucalyptus trees. Initially my father rode there on horseback from Melbourne, stopping at Box Hill on the way. Later, he bought an open car (probably about 1917) and travelled more comfortably. My mother, however, refused to travel to beenak, once the car was abandoned for the railway.

‘Merriyula’ was the name of the house on top of this mountain. There was no electricity, no gas, no water services nor other utilities of modern life. Water was pumped up from a dam about a mile away, by a four-cylinder hydraulic ram. With produce from the vegetable garden and the farm the house was self-supporting. Lighting was by kerosene lamps. I suspect the fire which destroyed the house (the family was in residence) started in the lamp room. My father would light the lamps every evening. Nothing remained of the house except the brick chimney and the large iron stove.

At the entrance to the house property were two giant sentinel trees. I am amazed at the work, which must have been involved in establishing this property. I am thankful that I had the opportunity to spend holidays there.

My father, Frederick Emil, is not recorded in Baptismal files (as far as we know). This is because my grandfather, Julius Emil, lived with a ‘common-law’ wife, Mary Noble, née Piper. This stable relationship produced several children. The reason for the, at the time, unconventional arrangement, seems to be that Mary Noble (my grandmother) was actually married to Mr Noble (untraced) and a woman could not obtain a legal divorce in the manner familiar to us today. Their union appears to have been a happy one, notwithstanding, and in his will, Emil speaks with affection of the woman who has shared his life, and bore his children. My grandfather returned to Germany, perhaps on business, in 1874, and died prematurely at the age of 49 years. He thus lies in the land whence he came. He is the forefather (with his English common-law wife) of all the Thonemanns in Australia and Great Britain. There were nine children of the union (possibly a few step children) but only four survived into the twentieth century.

My father married twice. His first wife was Margaret née Service. She bore him 3 children. Emil Howard, born 1891, fell in France, in the First World War, and his name is recorded at the famous monument near Arras by Sir Edward Lutjens. The other two sons enlisted also, but survived.

My father married for the second time in 1913, having travelled to Britain, and met a young Scottish lass from Glasgow. How they met, I do not know, but it was a very propitious match for a respectable, but not particularly grand, middle-class Scottish family, with the name of Fyfe.

At 18 years of age, my mother left her native land for the other side of the world, never to return, except for brief holidays. Herr husband was considerably older than herself.

Mabel Jessie Thonemann bore 4 children, three sons and one daughter. The four in order of birth were Frederick Fyfe (1914), Peter Clive (1917), Gwenda Hope, and Ronald Howard. The eldest (my brother Frederick) is dead, and this makes the writer the oldest surviving son of the Australian branch. All four children have families.

Frederick Emil spend his life in Melbourne, Australia, except for brief visits to Great Britain. With his second wife, he lived in a suburb of Melbourne called Kew. My brother Frederick, and I attended Melbourne Grammar School, as our father had done, and by this time the family lived at 33 Burke Road.

My father retired in 1930, living until 1939 (long enough to see his two sons graduate from Melbourne University). It is of interest that our family learnt nothing of our ancestry, nor ever met my father’s sister, Minna, (although she lived in Melbourne). This can be explained by the fact that war broke out, in 1914 with Germany, my stepbrothers serving on the Allied side.

I was born on June 3rd, 1917, in a house named ‘Rathgawn’, at Kew, Melbourne. It was a large rambling house, later to become a residence for the Salvation Army. We later moved across the road to a smaller house. (A childhood memory is my mother throwing a rug over a yang bird, which visited us while we were having tea on the lawn. The bird was put in a cage, where it seemed perfectly happy.) I never met my paternal grandparents.

My father, as I have said, never discussed his relations, living, or dead, nor did he discuss his financial affairs. In 1936 I began a physics degree at Melbourne University, living in a one bed roomed flat. My brother Frederick joined the university debating team, which travelled the world, and we saw little of each other. My sister Gwenda, now 10 years old, was at school. (As the only girl in the family, she was teased mercilessly.)

I enjoyed my university days. I played billards, occasional tennis, and in particular was a member of the university skiing team which visited Mt. Hotham.

In 1940, when war broke out, I was directed to work at the Munitions Supply Laboratories at Maribrynong, Victoria, and stayed there until 1942. I left to join the research department of Amalgamated Wireless, at Ashfield, near Sydney. In 1944, I was accepted by Sydney University to read for a Master’s degree in Science. (Victor Bailey was the head of the department.)

It was in Ashfield that I met my future wife. We have two children, a son and a daughter. My son, a schoolteacher in London, graduated from Balliol College, Oxford.

Wales 2000

Peter Clive Thonemann

Emeritus Professor

Universität von Wales

This article “The Thonemann branch in Australia” is from the book “Confessor of the Last of the Habsburgs” by Helena Fyfe Thonemann, page 110 until 130.